PROTODISPATCH

A monthly digital publication of artists’ dispatches on the life conditions that necessitate their work.

OCTOBER 17, 2024

OCTOBER 17, 2024

VIBRATING SENTENCES

The mysteries of finding ourselves in the trap doors of language. Artist, writer, and educator, Kameelah Janan Rasheed contemplates the textures and opacities of language as liberatory acts.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed

“[l]et this text be as alive as you are alive.”

– Gumbs, Alexis Pauline, M Archive: after the End of the World

Letters, words, and sentences are not just static symbols on a page. They are alive. A twerking letter “i” pops so hard that it knocks the superscript dot to the ground, leaving behind a decapitated letter that now resembles a stunted “l.” This lively transformation of a letter into another, more playful form is just one example of the living nature of language. A cursive sentence: letters running hand in hand as they approach the line break, a casual entanglement. A daisy chain of soft kisses between letters forms the connecting ligature, a tender and living way of linking words. The paragraph’s rowdy punctuation forms a maze, leading the reader astray in an attempt to finesse a promotion from supporting character to protagonist. A faded line of photocopied text is struggling with the breakup between printer toner and substrate – the struggle between ink and paper. A footnoted translation of the word “silly” gets into a fight for not disclosing its previous etymology. I imagine the letters having a life with one another — dancing, breaking up, rebelling, hiding, fighting, tricking, and loving. What if it’s like a Toy Story, and when we go to sleep, the letters on a page get up and have a whole life of their own, independent of our wishes? What can one make of the interior lives of letters, words, and sentences? Saying this feels fantastical, childish, and naive. But I am all of these things. The text makes me giddy, and I feel like the backside of a pair of chartreuse green corduroy pants.

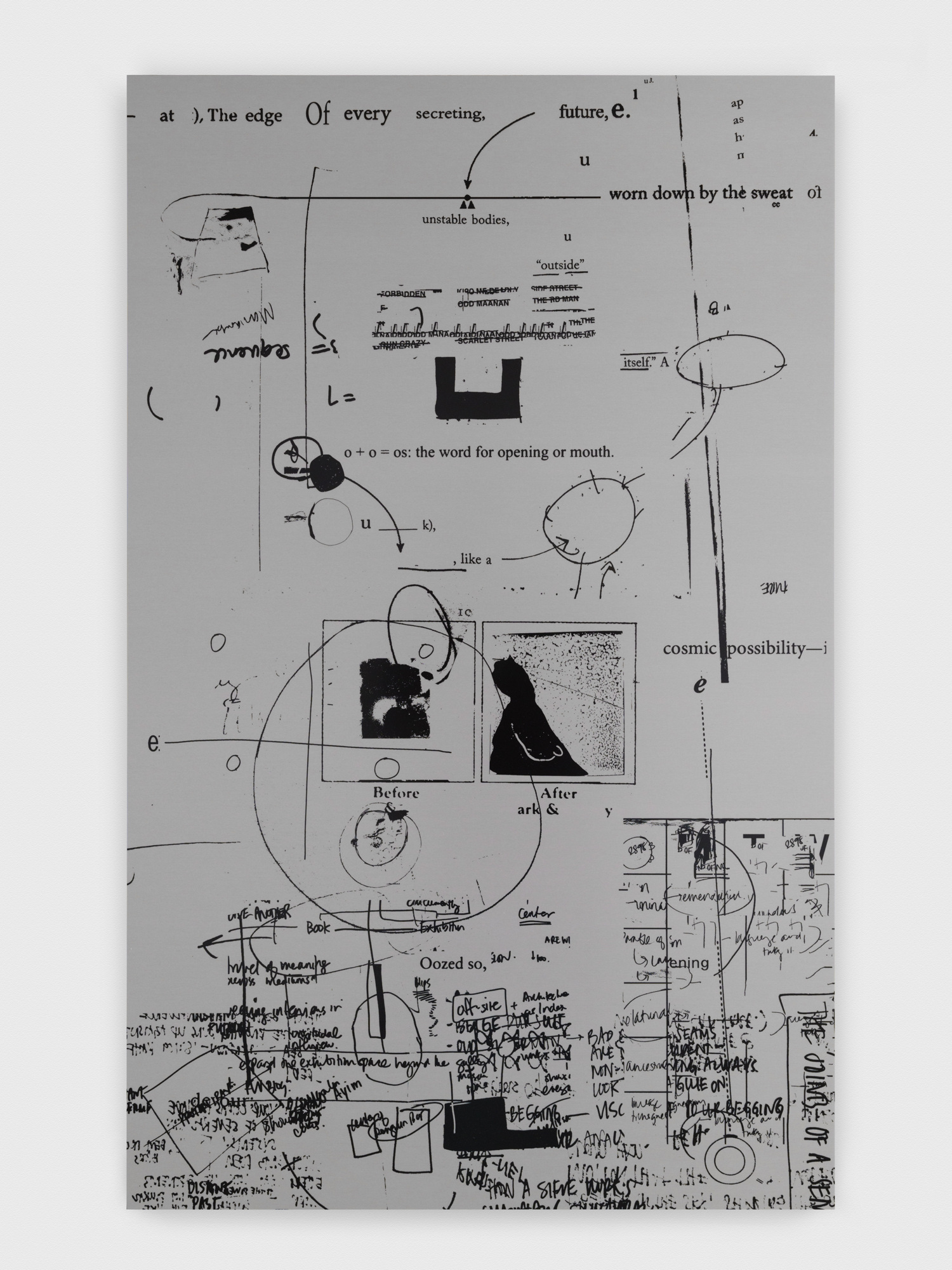

As a child, I spent hours downloading fonts and exploring the system fonts to find the suitable typeface to express best the interiority of my name or the title of yet another book report. This was later suspected to be an early symptom of Obsessive Compulsive Behavior. I only started writing the assignment once I arrived at the optimal handwriting and typeface for the prompt. As such, there were indeed days when the paper wasn’t written because not being able to find the typeface or handwriting was the most optimal carrier. It would be odd to send your five-year-old outside in an ill-fitted jumpsuit. Likewise, I don’t want to send my words “outside” (my brain?) without the appropriate attire. I’d never send that sentence outside with a flared serif, tight kerning, and shallow descenders when we know she needs to wear a bracketed serif with irregular kerning and exaggerated descenders so she feels like gushes of wind are blowing through her apertures. This carried on with substrates as well. Before I learned in 2020 that I would much instead write spatially across a large wall or sheet of paper, I would spend hours searching for the most hospitable host or substrate. Is it paper, skin or metal? My mother recounts a story of one of my first political movements — convincing the Kindergarten teacher to invest in better poster paint and paper because the substrate's thinness caused leakage. The substrate is part of the content, not just a passive surface. In geology, a substrate is the rock or sediment surface where chemical and biological processes occur. Likewise, in biology, it is the surface on which an organism lives, and enzymes can act. Substrates, like stages, are occasions. All stages have their affordances: not all stages or substrates can be host to a sentence’s performance. Sometimes, we do not need the vellum paper or the acetate sheets; we need skin, fabric, sky, or wall. Which substrate is the best host for this performance?

This sentence comes in the form of an open tangle.

– Moten, Fred. Renee Gladman and Fred Moten: One Long Black Sentence. United States: Image Text Ithaca, 2020

Letters vibrate. They hum. They buzz. They are in motion. And most of all, they are living — metaphorically. But who needs more metaphors? Maybe we do not need more metaphors, but we rely on more metaphors because it is one of the limited technologies we have to describe language – we use language to describe language. I am writing an essay about writing an essay. The lasso cannot lasso itself. In The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-human World (1996), David Abrams writes:

Every attempt to definitively say what language is is subject to a curious limitation. For the only medium with which we can define language is language itself. We are therefore unable to circumscribe the whole of language within our definition. It may be best, then, to leave language undefined, and to thus acknowledge its open-endedness, its mysteriousness. Nevertheless, by paying attention to this mystery we may develop a conscious familiarity with it, a sense of its texture, its habits, its sources of sustenance. (Abram 1996, 52)

In leaving “language undefined…acknowledg[ing] its open-endedness,” we are reminded of the sociality of language. I do not only mean sociality in terms of language being learned through social interactions; I am also thinking about sociality as the relationship between words on a page as a social arrangement (consider concrete and experimental poetry where the relationship between the substrate and text is one of collaboration, negotiation, and friction). This social arrangement is perpetually undone through the writer’s revisions and by the reader’s perception of the text (see: Umberto Eco’s invoking of the reader’s “ghost chapters”; poet and quantum mechanics researcher Amy Catanzano might call this an example of the observer effect where “the observer affects the observed…a reader can affect a poem’s meaning through interpretation”).

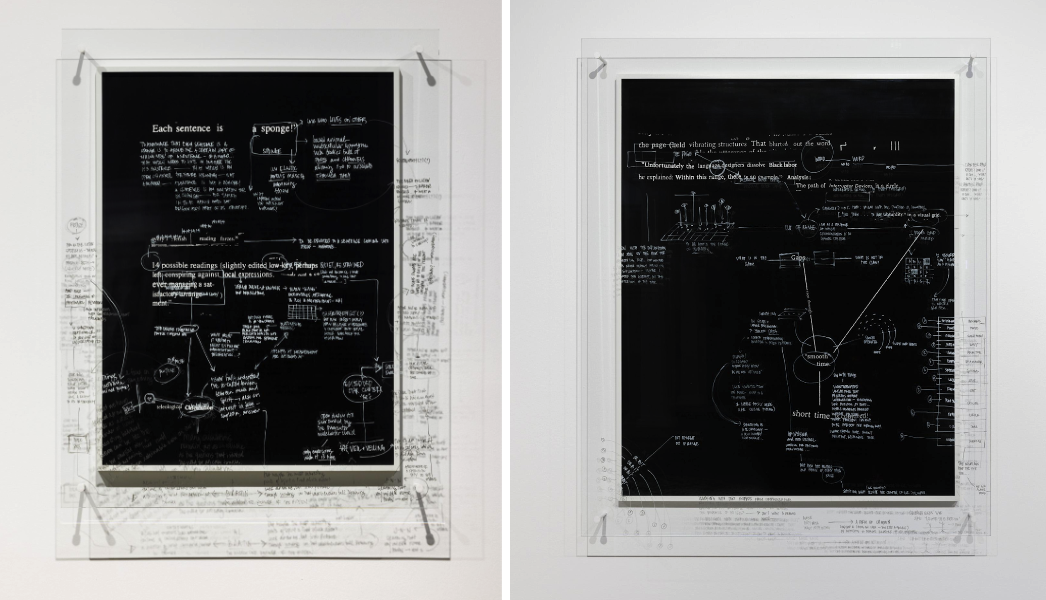

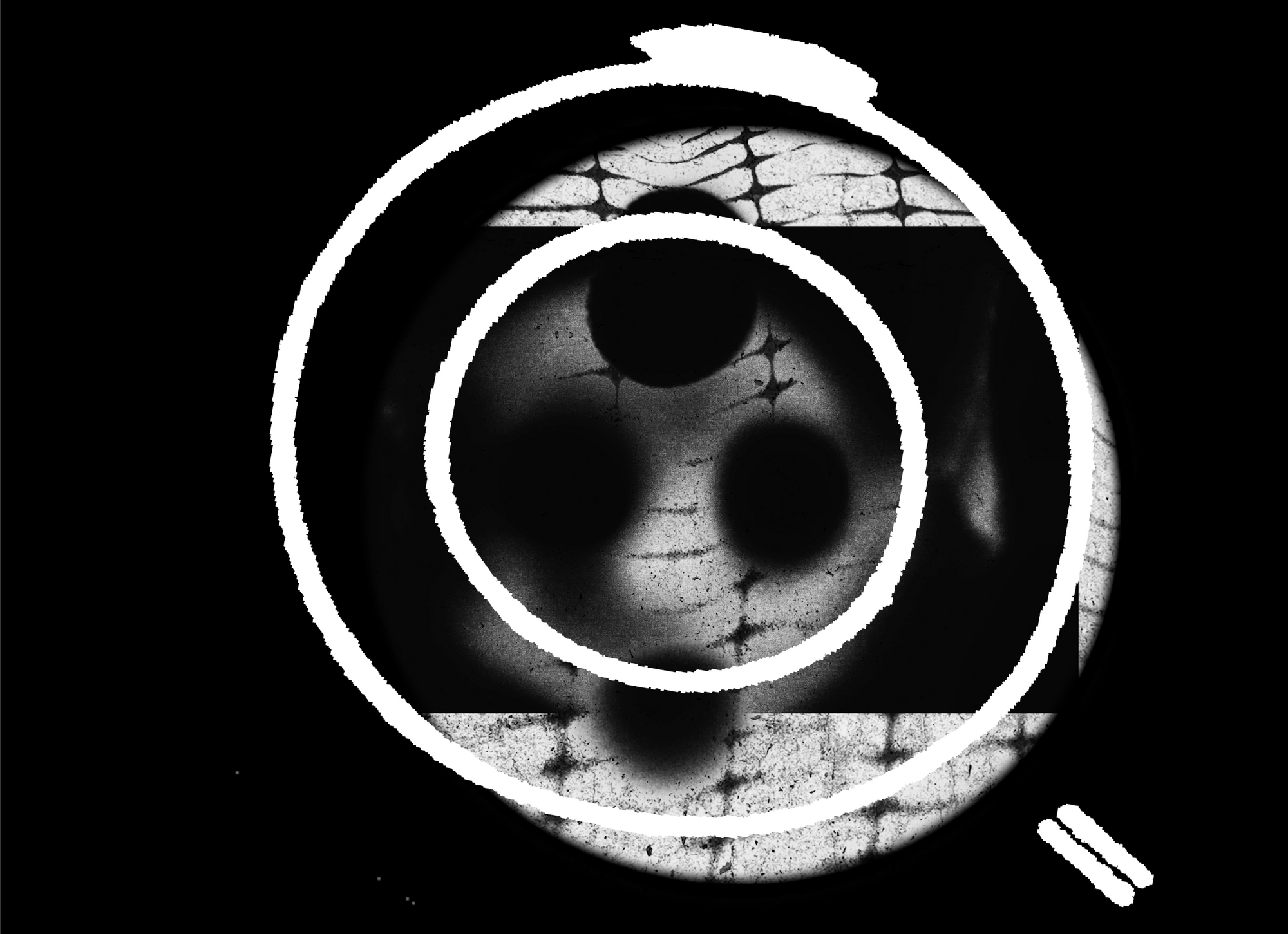

Language is undone because we are not done. (Cue Lucille Clifton’s poem, i am not done yet where she writes to us: “as imminent as bread”) The politic of being undone – and maintaining that volatile state as a stay against enclosure is something Ashon Crawley calls us to “tarrying with concepts” and “sustaining undoneness” in Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (2017). And this brings something to the fore that Crawley shares in That There Might Be Black Thought: Nothing Music and the Hammond B-3 (2016) with this question: “what if tones weren’t reaching for resolution or completion but were perpetually, ongoingly, open?” This question is followed by a gentle invitation: “tones that are not simply moving toward resolution but are on the way to varied directionality—not simply in a linear, forward progression but also vertically, down and up, askance and askew...Would not this reaching, this movement toward without ever seizing the beyond, allow for the emergence of ongoing anticipatory posture, an affective mode of celebratory waiting?” This gesture of reaching “without ever seizing” offers us the choice to do something other than completing the sentence while writing or seeking perfect comprehension while reading. This “anticipatory posture” that Crawley speaks about is the posture of possibility that animates my relationship to the writing process. Writing as a performance of possibility. Writing as a refusal of compulsory coherence. He reminds us again, “[a]s centrifugitive, black thought does not privilege any notion of centering but is constantly erasing, revising, undoing, unsaying any resting on or in fullness, completion.” I write across walls and layers of substrates such that that stage (substrate) becomes a field of geological marks mapping different versions of myself and my relationship to the text. It is not so much a palimpsest as much as it is a notation for a choreography of “erasing, revising, undoing, [and] unsaying.” A score for a vibratory, something. Jiggling marks on a page. As my work below reads: “The page (held vibrating structures That blurted out the word” – the substrate trying to restrain the word becomes a futile device.

(R) - The Page Held (Vibrating Structures), 2020, Gicléeprint / Archival Inkjet Print, 127 x 101 cm; Call and Response I, 2023, Glas, Stahl, Marker / Glass, steel, marker, 147 x 121 cm.

Installation view of the exhibition Schering Stiftung Award for Artistic Research 2022: Kameelah Janan Rasheed – in the coherence, we weep at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2023; All works: Courtesy the artist and NOME Gallery, Berlin. Photo: Frank Sperling.

In Fred Moten's 2015 journal article Blackness and Poetry, he writes:

We’re supposed to derive from the work, in its completeness, some sense of its rule. But what about the openness of the work, its internal sociality as well as the social relations of its own production, which not only escape but also succeed the works seizure…

Now, all of us who have read Fred Moten know that Moten loves page-long sentences. When I first began to read his work, I enjoyed chasing the tail of the sentence. Each sentence felt like a speculative incubator, an infinite set of nested parentheticals. I remain intrigued by “the social relations of its production” and “internal sociality.” Producing writing requires social relationships in its production, distribution, and revision. Consider a piece of published writing - maybe even this one. I am trying to gain traction, to find the handles on the words so that I can wrestle them into a state of glorified submission: this written text. Producing this work demands engagement with former selves, editors, text message exchanges, and more. Octavia Estelle Butler talks about this “primitive hypertext” or this shuttling between different texts in the production of her novels during a 1998 interview with Samuel Delany at MIT. Fred Moten, writing about Renee Gladman’s work in their collaborative publication One Long Black Sentence (2020), notes the “auto-correct resists a little, sometimes won’t let me do what I want to do, and then, after I finally defeat it, it leaves a little scar, underlining, marking what it takes to be mistaken.” This scar marks this sociality between the writer and the word processor, much like track changes. Moten echoes the openness that Lyn Hejinan summons when she speaks about the “open text” and Umberto Eco's surfacing of “the open work” – all are invitations to inhabit and cruise the holes in the text.

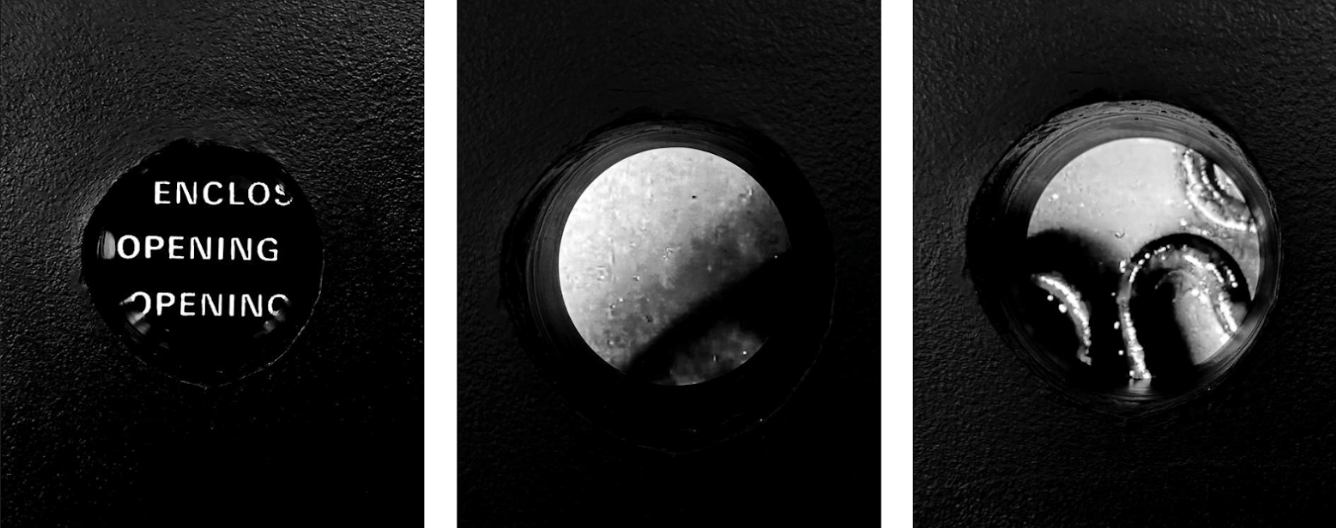

Pope.L’s Hole Theory (2002) is an articulation that also evades articulation. Pope.L offers holes as “occasions,” “a voodoo of nothingness,” as opportunities to consider our relationship to lack and the impossibility of knowing or possessing. And at one point, Pope. L offers: “Maybe I should substitute 'Theory'/With the word: 'Practice.'/Or: 'Catechism.' OR: 'Homework.'” We practice holes. Holes are praxis, not prattle. He writes: “Beneath this [redacted] sentence [handwritten above redaction] is a hole.” How do we imagine Pope.L’s redaction as a hole alongside the hole he points to under his sentence? It becomes something like a set of nested holes – a black hole that swallows another black hole. What we know of black holes is that if we get too close, we will not escape their gravitational force, leading to spaghettification. To get close to the holes of a text is to accept the risk of a particular kind of obliteration and undoing. To read is to seek an intimacy that may ruin us. I tried to get close to the roaming holes in Clarice Lispector’s Agua Viva (1973) and I am still trying to climb away from the event horizon because I know once I cross it, I cannot return – at least not as a self I am familiar with. In Elvia Wilk’s essay collection Death By Landscape (2022), she has an essay toward the middle of the book entitled Funhole. Here she reminds us to think about black holes differently:

...entering may not mean annihilation, but transit. The journey may transform the participant to the point where a trip report would be moot, but that does not mean there is no passage to be made. Perhaps a passage one cannot report back from is the most important kind of passage.

Not everything we experience can ready itself for language, nor should it. Sometimes, we go on quests wherein only we can be the traveler. My writing becomes little trinkets I have managed to carry back on that quest – the matter I am able to conjure from the ephemeral fog. Wilk tells us her efforts led her “across an event horizon: I plummeted, am still plummeting, into a particular kind of void.” I always want to cross the event horizon. I always desire a void more than I desire coherence.

…as if the line bore its own diacritical mark inside itself as a tendency for waywardness, line always about to go off like an (un)held note of David Murray’s, that Abbey-flared offness from a choir stayed up ahead to meet it.

– Moten, Fred. Renee Gladman and Fred Moten: One Long Black Sentence. United States: Image Text Ithaca, 2020

Building the sort of dangerous intimacy with a text is reading the words and gleefully taking an “inferential walk.” Umberto Eco’s “inferential walks” are like cruising the implicit articulations in a text – filling in the holes with our associations to create “ghost chapters.” In The Role of the Reader (1979), Umberto Eco writes about “inferential walks” as a spatial activity, a choreography of wandering: “to ‘walk’ so to speak, outside the text in order to gather intertextual support.” (32) Inferential walks, much like Pope.L’s invoking, “Beneath this sentence is a hole,” encourage us to consider language as a series of hideouts, pockets, and cavities. Thus, our relationship to text becomes, at least for me, less about uncovering the contents of these cavities, and more about a willingness to be lured to the edges of the holes knowing that you may never make sense of it. The navigation of language’s hideouts and trapdoors requires a wayfinding technology not so much toward coherence but toward an errancy as is described in Betsy Wing’s translator notes in Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation (1990): “Errance for Glissant…is not idle roaming, but includes a sense of sacred motivation” – a sacred motivation to wander without embarrassment – to dance with the holes or as as Pope.L writes:

Hole Theory is guided

By blindness.

Blind folk cannot see

Yet they have the courage

To move about in the world

Bumping into things,

Narrowly missing things,

Trying to get things done

I look to Saidiya Hartman for this technology of “sacred motivation.” In Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019), she offers:

Waywardness: the avid longing for a world not ruled by master, man or the police. The errant path taken by the leaderless swarm in search of a place better than here. The social poesis that sustains the dispossessed. Wayward: the unregulated movement of drifting and wandering; sojourns without a fixed destination, ambulatory possibility, interminable migrations, rush and flight, black locomotion; the everyday struggle to live free… Wayward: to wander, to be unmoored, adrift, rambling, roving, cruising, strolling, and seeking. To claim the right to opacity. To strike, to riot, to refuse. To love what is not loved. To be lost to the world. It is the practice of the social otherwise, the insurgent ground that enables new possibilities and new vocabularies; it is the lived experience of enclosure and segregation, assembling and huddling together… It is a beautiful experiment in how-to-live.

Here, the “sacred motivation” as we stroll and seek is not perfect comprehension as much as it is “enabl[ing] new possibilities and new vocabularies” – an otherwise.

“To begin with the otherwise as word, as concept, is to presume that whatever we have is not all that is possible. Otherwise [...] The otherwise is the disbelief in what is current and a movement towards, and an affirmation of, imagining other modes of social organization, other ways for us to be with each other.”

- Crawley, Ashon. Otherwise, Ferguson, Interfictions Online, 2016

I arrived at my writing practice in the pursuit of an otherwise. It is not about writing speculative fiction; instead, I am invested in exploring how breaking the expected structure of language can be a rehearsal for another sort of existence. Can a sentence do more than describe? John Austin of Ordinary Language Philosophy framed the concept of “performative utterances” – that the sentence does not describe but changes the reality it describes. He offers “I do” at a wedding ceremony as an example – the utterance announces a new reality rather than explaining this new reality. Maybe I am after a performative experimental grammar where a run-on sentence isn’t so much “bad grammar” as much as it is an insistence on the possibility of a feral existence that is not hemmed in on all sides – something like what Saidiya Hartman calls “black locomotion.” Moreso, something like Tina Campt’s insistence on a “grammar of black feminist futurity” or “the performance of a future that hasn't yet happened but must.”

In One Long Black Sentence (2020) I am struck by Moten and Gladman’s engagement with questions of “black locomotion” and “unregulated movement.” Moten asks two questions in conversation with Renee Gladman’s work:

“Is there refuge in the sentence?”

“Is there an underground railroad in the sentence?”

Sentences are the cover story for under-the-radar behavior, a series of trapdoors for the reader to fall through – straight into the hole beneath the sentence. Might the underground railroad in the sentence be the path of radical and liberatory exploration? A comma that not only separates clauses but creates a pathway to a speculative future an “otherwise”? A subscript that sends our eye downward to imagine the proximity between the bottom of the number “8” and the crown of a letter as the measure of the possibility of something other than what we have now? In chapter two of Sarah Jane Cervanak’s 2021 book Black Gathering: Art, Ecology, Ungiven Life Cervanak explores the work of Samiya Bashir and Gabrielle Ralambo-Rajerison within the context of quantum physics and Amy Catanzano’s description of “quantum poetics.” Cervenak writes:

I ask, then, if, following Catanzano, the poem, engaged as a scene of quantum causes and effects, shows how language always points to an extra-empirical elsewhere, then might the spacing around words also allude to a something off the page? [...] —the spacing around words, after passages, on the page—another occasion of cosmoaesthetic and cosmopoetic meditation and coexistence?

Might the “something off the page” be the otherwise? Is this liberatory possibility what we find when the white spaces of a poem invite us to wander off the page to pursue something not yet? Is the “extra-empirical elsewhere” what we are seeking? She continues:

Moreover, taking the page as seriously as the words, a move required by the authors’ typographic and imagistic innovations, makes another way for Black gatherings’ imaginative release from empirical (and perhaps typographic) form and elucidates how writing, and poetry itself, might beckon the somewhere else of such release.

Here the feral location of language of the page operates not only as an aesthetic offering, but also a collaboration between substrate and words to consider otherwise possibilities of Black gathering and ecstatic resistance in that refusal of enclosure. Later, Cervanak points to this otherwise as “the writing of ‘impossible’ sentences joined by what poet critic Dionne Brand asserts as poetry’s ‘pressure on the page, on space, on time’ [...] an aesthetic reencounter with the universe bears the potential for some nonextractive and noninscriptional reimagining.” I am taken by Brand’s insistence here – that when we write, we are not only languaging; we are exerting force against our current conditions as an enactment of a “grammar of black feminist futurity.” In reflecting on my 2020 print “Black people/want irony,” I shared that I want sentences to feel unfamiliar. Suppose we can read a sentence that bypasses the statistical expectations of collocation – this word must sit next to this word. In that case, we can consider the possibility of societal systems that bypass the historical expectations of those who do and do not survive. The work resulted from an accidental juxtaposition while installing work, and I love a revelatory accident. We desire a decade that does not rhyme with the last decade and encounters that break the rhyme scheme.