PROTODISPATCH

A monthly digital publication of artists’ dispatches on the life conditions that necessitate their work.

JULY 18, 2024

JULY 18, 2024

RHYTHM, VIBRATIONAL FORCE, AND ZOMBIES AROUND MOTION PICTURES

Writer/Artist Kridpuj Dhansandors questions the ecological precarity that is entangled within political traumas in Thailand via Motions Pictures, an installation by artist/filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

Kridpuj Dhansandors

Vibrational forces and cyclical rhythms flow through the memory of sediment from the Himalayas into the Chiang Saen district in Thailand. The earth's crust and the Naga, mythical, serpentine creatures, move through the archaeological corpses of an ancient kingdom in a time before the advent of official Buddhism and before the Siamese state tried to control that very northern kingdom. Motion Pictures, an installation by artist and filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, is a ritual that reawakens zombies, questioning the ecological precarity entangled with the political traumas of a patchy Anthropocene.

Sediment Ways and Memories from Weathering

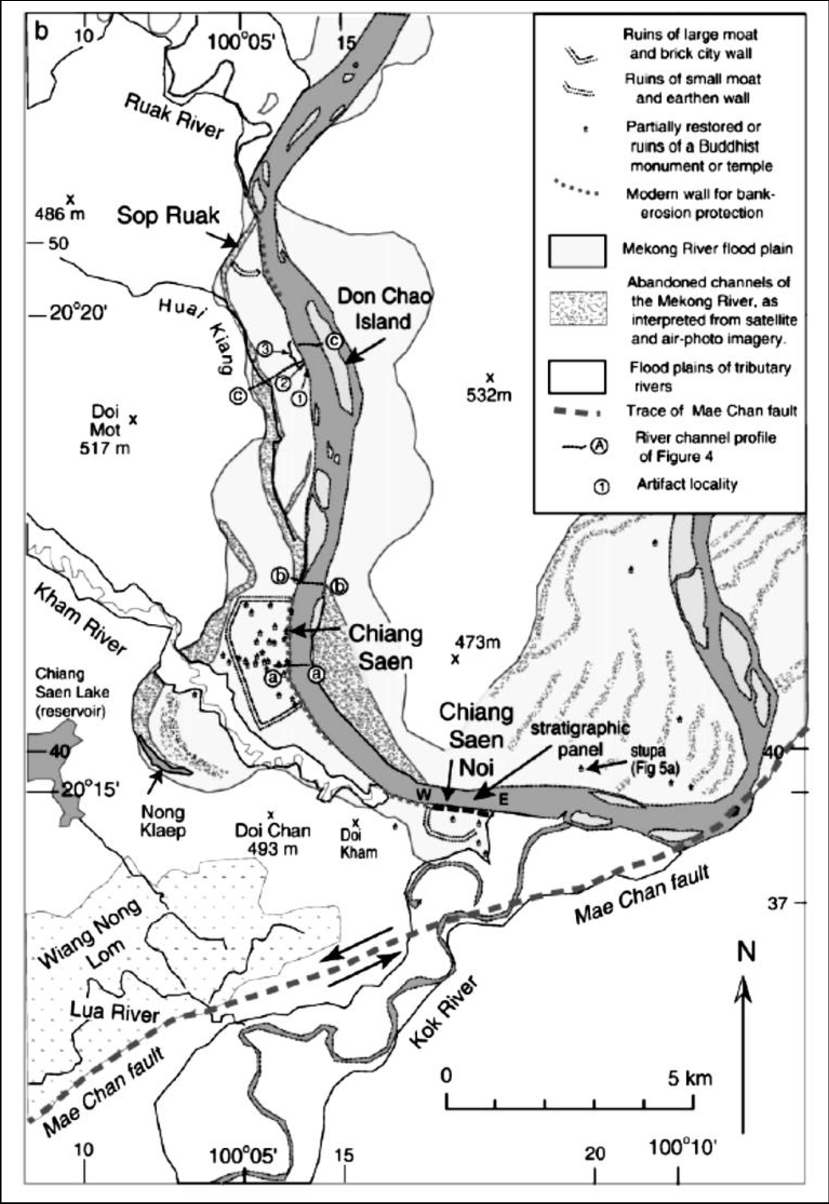

Sediments, from snow melt and the weathering of the upper Himalayas,1 flow from the Tibetan plateau, China, Burma, and Laos until they reach the Chiang Saen district in the Golden Triangle area of Thailand.2 The sediment flow rate at Chiang Saen is approximately 58.4 million tons per year. According to excavations by geologists in 2008, the Mekong River was formed by faults in the earth's crust. 1.7 million year old basalt flows have been found in the uppermost layers of sediment in the river, evidence that links to the Neolithic period. Artifacts from the fourteenth-century Lan Na Kingdom were discovered in the form of city walls that had eroded into the river.3

Movement and tectonic activities along the Mae Chan Fault cause the Chiang Saen floodplain to constantly expand.3 The construction of the Manwan Dam in Yunnan Province in 1992 has had an impact on sediment flow and river morphology, including fewer floods.4 The rhythms of seasonal flooding and sediment flows are natural processes necessary to the life of rivers, floodplains, fish migration, and mineral distribution.5-10

Impacts from dam construction also include the degradation of wetlands that are dependent on seasonal flooding.5 Wiang Nong Lom, is a significant wetland in the southern part of the Mae Sai basin, was formed by the movement of the Mae Chan fault, historically situated Yo Nok Nakhon kingdom during the legendary era of Lan Na history. There is no archaeological evidence has been found in Wiang Nong Lom to indicate the existence of the Yo Nok Nakhon kingdom, which collapsed due to an earthquake in 460 AD.11

Most of the sediment in Wiang Nong Lom dates back to the Holocene period,11 the beginning of the Neolithic era when humans began moving about 10,000 years ago.12 Natural sedimentation combined with human technology has since led to the dramatic degradation of wetlands in the Mae Chan and Chiang Saen districts of Thailand. A key factor is the acquisition of land by investors, leading to migration and competition for non-agricultural jobs.13 Sediment transport routes are responding to radical shifts in overdevelopment and large population migrations, which are a devastating part of interactions between humans and the ecosystem.6

Naga's Movement and the Control to Keep it Still

Like the very earth, the tale of Wiang Nong Lom as connected to the pre-Buddhist belief in the Naga (a semi-divine race of half-human, half-serpent beings that reside in the netherworld), is woven into the daily lives of people within these floodplains.14 Phaya Chai Chana, the unethical king who ruled Yo Nok Nakhon before the beginning of the Phraya Mangrai era, ordered his people to kill the white eel (mythologically representing the Naga’s children), which resulted in the collapse of his kingdom. Following the king’s edict, villagers captured the white eels/the Naga’s children and distributed them to the people to eat, incurring the Naga’s great wrath.15-16

The Naga, who live in the river,17 also influence the rain. The movements of the Naga are related to the fluvial landscape, earthquakes, and floods. A number of people consider themselves descendants of the Naga, which has shaped the sense of community in Chiang Saen.14 Naga are considered actors in the web of ecological change, political power, and economic growth.18

The great temple Wat Pa Mak Noh was built with non-traditional Buddhist ideas before the fourteenth century. Departing from the more classical plans seen later in Chiang Saen that were influenced by state-supported Buddhism, Wat Pa Mak Noh’s chapel faces the Wiang Nong Lom area. The stupa was built on the spot where local people believed the entrance to the Naga realm existed. By contrast, at Wat Pa Sak, which was built later, the chapel and main Buddha image face east.16 Mythscape and early belief systems weave together the unknown and humans’ desire to live respectfully with the land.16-17

The Naga, however, coexisted seamlessly with Northern Buddhism throughout history. The creation of Wat Pa Sak involved a combination of many cultures. Hinduism and Buddhism have influenced the concept of Dharmaraja and Devaraja as incarnations of Shiva, who lives in the Himalayas. Further, premodern communities or early states in the Chiang Saen area, especially before the fourteenth century, exhibited non-fixed forms of ranking for social interaction, which were consistent with the distributed power systems found in many prehistoric Southeast Asian communities. Although temples built after the fourteenth century were more hierarchical, including clear separation of spaces for monks and laypeople, horizontal elements remained.19

The co-existence of Buddhism with animism can be found in non-traditional Buddhism, such as that practiced by Kruba Bunchum, who was born in Mae Sai District, Chiang Rai in 1965. Bunchum influenced the beliefs of the Shan, Lue, Lahu, and Wa ethnic groups, as well as the Thai middle class and the Burmese Army. Ethnic groups incorporate Kruba Bunchum into their mythological beliefs, positing him as the savior of the Shan people or Lahu’s G’ui sha. This conflicts with Theravada Buddhism, which tried to control Buddhism in the northern region in the early twentieth century, leading to millenarism, which used the method of building religious sites to accumulate merit, challenging the Siamese state’s control.20-21 For example, in the late nineteenth century, local leaders of the Chao Upparat Khamtui competed with the Siamese governor over temple building. The former renovated Wat Phra Singh, while the Siamese governor renovated Wat Chanthalok Klang Wiang and looted important Buddha statues in Chiang Saen to destroy the legitimacy of the original local leaders.21

Rhythm of Buddha Statues Replicas

Motion Pictures (2023) is an on-site installation by artist Apichatpong Weerasethakul, in Thailand Biennale, Chiang Rai, 2023.[1] The installation consists of two rooms in a former schoolhouse with a double-projection video (titled Solarium [Ghost Screening Room] Side A and Side B), fabrics printed with paintings by Noppanan Thannaree and Amnart Kankunthod that slide back and forth, a holographic film, and a Buddha statue partially painted gold. “These scenes include the backdrop of Thai folk opera, curtains and white screen in the cinema theater, along with projectors, light and shadow in two and three dimensions. These elements combine into a collage, patching and layering in the classroom area, representing the consumption of time, darkness, politics, and dreams.”

Blue Encore, Moving Images, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Thailand Biennale, Chiang Rai, 2023. Video by Kick the Machine studio, courtesy of Thailand Biennale

Apichatpong's Motion Pictures coherently choreographs its meanings through the vibration of Ban Mae Ma School building, Mae Chan fault and the rhythmic movement of sediment in wetlands and rivers, Nagas, and displaced workers. These movements reject the stationary. Zombie and Buddha images are the refrain in a rhythmic pattern that brings order to chaos and connects bodily forces with cosmic ones.22 Representations reproduced in infinite cycles thus offer a spatial and temporal potential for transformation and resistance to fixed identities. At the same time, the unconscious repetition of rituals, social norms, and power structures may reinforce the ideology and create a sense of unquestionable reality.23 Repetition is not a pursuit of perfection and hierarchy, but rather suggests that behavior repeated in ordinary daily routines could become a ritual of caring for both the individual and the community.24

The physical movement of the Phra Phuttha Sihing and the Emerald Buddha (the latter was discovered at Wat Pa Ya, in the Mueang Chiang Rai district) throughout Southeast Asia embodied its political role due to the belief that there are revered ghosts residing in the Buddha statue,25 which contributed to the power, wealth and protection to holders of Buddha images and statues. The sacred power of the Emerald Buddha was used to solidify the power of the monarchy, military, and Theravada Buddhist institutions. For example Phraya Chakri (Rama I) stole the Emerald Buddha from Vientiane and took it to Wat Arun Ratchawararam in 177826 Following that, the Maha Sura Singhanat (King Rama I’s cousin) looted Phra Phuttha Sihing to the Phutthaisawan Throne Hall in 1795 after the victory over Chiang Mai, although there is some debate as to which Phra Phuttha Sihing is the original,27. There is currently historical evidence supporting the authenticity of three different statues.28

Reproducing Buddha images is part of creating Samakki and Barami.21 The Buddha Vimokkha, for example, was created in 1985 by Luang Pu Ngon (who is the teacher of Kruba Bunchum and was inspired by Kruba Sriwichai30). After its creation, more than 200,000 replicas were sent to schools across the country, and an amulet version was given to soldiers stationed at Phu Hin Rong Kla base, which used to be the center of the largest and most important base for spreading communism in the northern region,30 as well as many other places.31 Two Buddha Wimokkha are enshrined on a Naga pedestal at Ban Mae Ma School, Chiang Saen district, Chiang Rai. In Weerasethakul's Motion Picture, placed in front of the green building, the Buddha Vimokkha challenges visitors by making it impossible to tell which one was there before and which one was newly placed, with one facing east, and the other one facing west.

Ban Mae Ma School was built in 1960,32 during the Cold War, when the North and Northeast were hotbeds of communism. In response, the Theravada Buddhist Sangha system was utilized as a state apparatus for creating national identity and resisting communism.33 Ban Mae Ma School is not far from Doi Sa Ngo, which is the home of the Akha people.34 Ethnic groups involved in the major opium trade of the 1950s were supported by the government and the Chinese Kuomintang military group in exchange for benefits. Opium’s popularity gradually waned until the late 1990s, due to the rise of amphetamine use.35

During the Cold War, however, the northern border region was of concern to the Thai government because it was an autonomous zone for communists in southern China, leading to cooperation with the US government in establishing the Border Patrol Police. Along with the rhetoric of “Chao Khao” (“hill tribes”) being uneducated and in need of assistance with the need to preserve the hierarchical power of the Thai state through the education and public health systems, Thaiization intensified in the 1960s through the criminalization of opium, creating a ethnic armed force to join in the fight against communism and resettlement of ethnic groups.36

Ban Mae Ma School was closed in 2007 due to the small number of students which caused students to be transferred to the sub-district school. In recent years, the school has been used to host a Buddhist study session for monks every Thursday.32

Repetitive Corpses and the Conjuring Ritual

Motion Pictures (2023) also includes Ok Bab Nai Jai (Designing in the Mind) or Blue Encore, a group of landscape paintings of the Chiang Rai forest, blue tree and the nowhere road, which is the view from behind the driver. Three images from Chiang Rai artists Noppanan Thannaree and Amnart Kankunthod were scanned and printed onto moving curtains resembling Thai folk drama theatrical backdrops. Behind this curtain is a whiteboard with the art lesson: the first step is “Designing in the mind” and the final step, “Repeating practice to be better than before.”

In the adjoining room is Side A (Ghost screening Room), a looped video, which is a repeat of the 1981 Noppol Gomarachun film Phi Ta Bo.[2] Apichatpong's works embodied the hypnotic trance of the audiences, similar to the zombie state. In doing so, it offers the potential to observe serene aesthetics, as both a way to escape from reality and to understand the Anthropocene as a form of expression long associated with the history of imperialism,37 and dissolves the duality between humans and zombies. The corpse power is therefore more than a symbol of human loss or social critique.38

When we walk into the Solarium (Ghost Screening Room) Side A, we find a chair to sit and watch, and an old table with cobwebs, reminiscent of the scene where the character Aunt Jen walks into an abandoned classroom in the middle of the night in the fantasy thriller film Cemetery of Splendour (2015). She contemplates a phallic-like creature that has been castrated or made impotent. Her status is thus vacillating between young and old women, human and machine due to her disabled leg, and constrained in a liminal parasomnia due to the patriarchal sovereignty that has made her sleepy and sluggish. She is like a zombie in a school that has been turned into a hospital to care for soldiers who came down with the sleeping sickness, along with a governmental excavation project of the ancient kingdom around her childhood school.

Behind the double-paned glass screen is a light projection room, where there were no chairs to sit on and no sound effects, but we felt, from the vibration of the school building, as if we were watching a phantasmagorical folk drama behind the scenes. In this room, we see the refracted image overlaid in two layers, unlike in the Solarium (Ghost Screening Room) Side A where the image is sharp due to the holographic film. The double vision calls into question the refraction, which refers to waves bending as they pass from one medium to another. This bending is a result of the change in the wave's speed and can be explained by classical physics principles.

In her book Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (2007), Karen Barad suggests that diffraction, creating three-dimensional images in haunting holography by bending or spreading of waves as they encounter an obstacle or pass through an opening, reveals the light as an agent. Knowledge creation comes from interactions and differences and resists the idea that truth is a passive entity waiting to be discovered.39

This clash between classical physics (e.g. refraction) and quantum mechanics (e.g. diffraction) creates the topology of a non-Euclidean space where boundaries are not sharp but rather fuzzy and constantly changing. This space is in contrast to the reflection in the mirror, it is a methodology that attempts to compare with reality and is obsessed with authenticity and originality.39 It is a legacy of humanity that separated the Anthropocene from the Holocene era around eighteenth century,12 following which humans began colonizing.

A hologram is created by a process of enfolding information into a pattern of waves, which can then be unfolded to reveal the original image. This continuous process reveals a dynamic cycle of enfolding and unfolding, and the interconnectedness of materials emerges from their interactions with the world.40 These movements challenge the corresponding perception that things exist as separate and independent entities. Our disabled and trembling bodies interact with crumbling school buildings, zombies, Buddha statues, Naga, and the sediment in the river. Motion Pictures situates the ambiguous space of things, challenges the pre-given world,41 and constitutes a crystallized time of the body’s liberation from mechanical Theravada habitualness, which were influenced by the neocolonial regimes that spread patchily across nation-state borders in mainland Southeast Asia. Apichatpong's cacophonous and visual practicalities invite us to ponder the ethos of co-dependence in inhuman assemblages.17

Footnotes:

[1] Motion Pictures (2023) is an art installation by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, displayed at Ban Mae Ma School, Chiang Saen District, Chiang Rai Province, as part of Thailand Biennale Chiang Rai from December 9, 2023 – April 30, 2024, co-curated by Rirkrit Tiravanija, Gridthiya Gaweewong, Manuporn Luengaram, and Angkrit Ajchariyasophon as curators, inspired by the Buddha images in the opening the world posture at Wat Pa Sak, which tells the story of Gotama departure from the heavenly realm after pleasing his mother. Gotama performed a miracle by opening the three worlds, namely the divine world, the underworld, and the human world, to be seen in full. The Naga came to welcome the Lord Buddha by spraying fireballs, which is The End of Buddhist Lent Day when monks can criticize each other, regardless of rank and age. The event's logo, five eyeballs, was inspired by a mystical four-eared, five-eyed creature, Sihuhata. Local legends tell the story of a miserable herder, Thukata, who became a righteous king because he adhered to the four Iddhipada and five precepts, linked to Sihuhata. The logo appears to be an attempt to involve local storytelling to challenge the Siamese colonial regime that has existed since the early nineteenth century.

[2] The original film tells the story of Kampon, a rich scientist who tried to find eyes for his wife who lost her sight in a car accident. His subordinates work in exchange for drugs to find potential victims, including women and old men from nightclubs. Kampon was not satisfied until by chance met Phon, a young, unemployed, displaced working-class man, looking for jobs on the outskirts of Bangkok, who repaired Kampon’s car. Kampon fell in love with Phon’s beautiful eyes. Kamphon made a deceptive plan to hire Phon in order to trick him into an operating room to have his eyeballs removed, which resulted in his death. Kamphon brought Phon’s eyeballs to his wife in hopes of repairing her eyesight, after years of home confinement. Unexpectedly, the botched eye operation transformed Phon into a zombie. Zombie-Phon came out to haunt Kampon and his wife every night until they were unable to leave their home, and became constrained in their upper-middle-class residence. Kamphon and his wife survived because of a questionable shaman’s holy thread. Phon entered the dream of the scientist’s wife asking her to destroy the holy thread, and later he was able to take his revenge. Phon’s eyes were plucked out of Kamphon's wife's eye sockets. Phon's eyes flew through the air and were stuffed into the villain/questionable shaman's eye sockets. Phon's wife was compassionate and asked to spare the shaman’s life, because she considered him, like Phon, hired to earn money to support his family. Phon had a final hug with his daughter before the sun rose in the morning, and his body burned and became part of the earth.

Phon became a non-human agent. B-movies from the 1970s often featured poverty and corruption, especially horror movies where female ghost characters seek revenge on men who have committed crimes. This was in line with women's daily struggles against abuse and injustice, in which the main audience were working class outside of Bangkok.43 Whereas in the 1980s, during the collapse of the Communist Party of Thailand44 and the subsequent economic hardship resulted in the emergence of low-budget films aimed at younger audiences.45 Phon, as a poor male ghost, was seeking justice from the middle class who benefited from capitalism flowing into Thailand during the Cold War.34 This embodied the middle class's fear of losing control over the working class and challenging the old social order.43 Phon breaks the line between "us" and "them," and questions the legitimacy of violence.46

Sleepwalking Phon resonates with other undead characters from 1980s Thai films, in which zombies were often portrayed as comic or even sympathetic figures, and raised questions about our coexistence with things we see as a threat.46 Although zombies originate in Haiti and represent the experiences of Black people who were enslaved by the French colonial regime in the early nineteenth century, the zombies narratives by revolutionists are often presented as disembodied zombies who challenged the existing social order and embodied resistance. This is in contrast to the zombies experienced by American soldiers who invaded Haiti in the early twentieth century, which resulted in Hollywood cinema that often presented zombies as passive and mindless. However, the film I Walked with a Zombie (1943), which featured the undead in contrast to Hollywood films,47 inspired Apichatpong to make Memoria (2021),48 wherein the director envisioned the actual slaves and questioned the audience's indifference to injustice.47

Reference

- Kumphorn R. The Mekong School. Effects, Changes, and What Remains of The Mekong River. The Mekong School; 2024 [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: https://mekongschool.org/en/ef...;

- WWF. General Information of the Mekong River. https://www.worldwildlife.org/...;

- Wood, Spencer & Ziegler, Alan & Bundarnsin, Tharaporn. (2008). “Floodplain deposits, channel changes and riverbank stratigraphy of the Mekong River area at the 14th-Century city of Chiang Saen, Northern Thailand,” Geomorphology 101: 510-523. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.04.030.

- Lu, Xi Xi & Li, Siyue & Kummu, Matti & Padawangi, Rita & Wang, Jianjun.“Observed changes in the water flow at Chiang Saen in the lower Mekong: Impacts of Chinese dams?” Quaternary International, 336.

- Laska, Shirley & Morrow, Betty. “Social Vulnerabilities and Hurricane Katrina: An Unnatural Disaster in New Orleans,” Marine Technology Society Journal 40 (2006), 16-26.

- Grundy-Warr, Carl & Lin, Shaun. (2020). The unseen transboundary commons that matter for Cambodia's inland fisheries: Changing sediment flows in the Mekong hydrological flood pulse. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. 61. 10.1111/apv.12266.

- Parrinello, Giacomo & Kondolf, George Mathias. “The Social Life of Sediment,” Water History (2021): 13.

- Klaver I. “3 Radical Water” in Hydrohumanities: Water Discourse and Environmental Futures (Berkeley: University of California Press; 2021), 64-88.

- Rice, J. “Controlled Flooding in the Grand Canyon: Drifting Between Instrumental and Ecological Rationality in Water Management,” Organization & Environment, 26(4), 2013, 412-430.

- Sneddon, Chris. “Nature's Materiality and the Circuitous Paths of Accumulation: Dispossession of Freshwater Fisheries in Cambodia,” Antipode 39, 2007, 167 - 193.

- Wood, Spencer H.; Singharajwarapan, Fongsaward S.; Bundarnsin, Tharaporn; and Rothwell, Eric. "Mae Sae Basin and Wiang Nong Lom: Radiocarbon Dating and Relation to the Active Strike-Slip Mae Chan Fault, Northern Thailand," Proceedings, International Conference on Applied Geophysics,November 26, 1994, Chiang Mai Thailand, 60-69.

- ตรงใจ หุตางกูร. นัทกฤษ ยอดราช. แอนโธรพอซีน (Anthropocene). [Webpage]. ศูนย์มานุษยวิทยาสิรินธร (องค์การมหาชน) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: https://www.sac.or.th/portal/t...;

- Hempattarasuwan, Nuttiga & Untong, Akarapong & Christakos, George & Wu, Jiaping. (2021). Wetland changes and their impacts on livelihoods in Chiang Saen Valley, Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. Regional Environmental Change. 21. 10.1007/s10113-021-01842-7.

- Moonkham, Piyawit & Cassaniti, Julia. (2017). MYTHSCAPE: AN ETHNOHISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF SPACE AND NARRATIVE OF THE NAGA IN NORTHERN THAILAND.

- ศูนย์วัฒนธรรมนิทัศน์และพิพิธภัณฑ์เมืองเชียงราย 750 ปี

- Moonkham, Piyawit. “Ethnohistorical Archaeology and the Mythscape of the Naga in the Chiang Saen Basin, Thailand,” TRaNS Trans-Regional and National Studies of Southeast Asia 10 (2021).

- Johnson, Andrew. (2020). Mekong Dreaming: Life and Death along a Changing River. 10.1515/9781478012351.

- จักรกริช สังขมณี. “The Mystery of the Almost Disappearing Naga: On Urbanization and Cosmopolitics in Bangkok,” MultipliCity, 2024, available at: https://static1.squarespace.co...;

- Moonkham, Piyawit & Srinurak, Nattasit & Duff, Andrew. “The Heterarchical Life and Spatial Analyses of the Historical Buddhist Temples in the Chiang Saen Basin, Northern Thailand,” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 70 (June 2023).

- Cohen P. “Charismatic Monks of Lanna Buddhism,” (Copenhagen: NIAS Press,; 2017),. 272.

- Irwin, Anthony Lovenheim. Building Buddhism in Chiang Rai, Thailand: Construction as Religion, dissertation, 2018.

- Rohman, Carrie. “‘We Make Life’: Vibration, Aesthetics and the Inhuman in The Waves,” in Virginia Woolf and the Natural World, eds. Carrie Rohman and Kristin Czarnecki, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011), 12–23.

- Coole, Diana, and Samantha Frost, eds. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics (Durham:Duke University Press, 2010).

- Aulino, Felicity. Rituals of Care: Karmic Politics in an Aging Thailand (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019).

- ศิริพจน์ เหล่ามานะเจริญ. พระพุทธสิหิงค์ เคยจะถูกนำไปประดิษฐานที่ โบสถ์วัดพระแก้ว วังหน้า?. Museum Siam [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: https://www.museumsiam.org/km-...;

- Laucirica, Teshan. The Emerald Buddha: Legend, Myth, and the Bedazzlement of History and Nation-Creation (University of Washington ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2023).

- ศักดิ์ชัย สายสิงห์. พระพุทธสิหิงค์ คือพระพุทธรูปขัดสมาธิเพชรในศิลปะล้านนา. ศิลปวัฒนธรรม [Internet] 2019 [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: .https://www.silpa-mag.com/hist...;

- ตำนานพระพุทธสิหิงค์. หอสมุดแห่งชาติ นครศรีธรรมราช. [Internet] [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: https://www.finearts.go.th/nak...;

- New Amulet. [Internet]. [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: https://www.new-amulet.com/Det...;

- อุทยานแห่งชาติภูหินร่องกล้า. การท่องเที่ยวแห่งประเทศไทย (ททท.) [Internet]. [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: https://thai.tourismthailand.o...;

- จุลสารโรงเรียนสาธิตมหาวิทยาลัยขอนแก่น ฝ่ายประถมศึกษา (ศึกษาศาสตร์) ปีที่ 2 ฉบับที่ 1. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024-05-09].

- โรงเรียนบ้านแม่มะ. Thailand Biennale, Chiang Rai [Internet]. [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: https://www.thailandbiennale.o...;

- Peleggi, Maurizio. Thailand: The Worldly Kingdom (London: Reaktion Press, 2007).

- ชาวอาข่าดอยสะโง้ ผวาหมูดำตายทุกวันนับร้อย ร้องปศุสัตว์ฯ ช่วยหยุดอหิวาต์ระบาด. [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: https://www.thairath.co.th/agr...;

- Ribó, Ignasi “Golden Triangle: A Material–Semiotic Geography,” ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 29 (2020).

- Hyun, Sinae. “In the Eyes of the Beholder: American and Thai Perceptions of the Highland Minority during the Cold War,” Cold War History 22, no. 2 (2022): 153–71.

- Graiwoot Chulphongsathorn. “Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Planetary Cinema,” Screen, 62, Issue 4, Winter 2021, Pages 541–548.

- Gardiner, Nicholas. Dead as a Doornail: New Materialism and the Corpse in Contemporary Fiction. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield, 2020.

- Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

- Bohm, David. On Creativity, ed. Lee Nichol (New York: Routledge, 1996).

- Varela, Francisco J. ; Thompson, Evan & Rosch, Eleanor (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991).

- Ainslie, Mary Jane. Contemporary Thai Horror Film: A Monstrous Hybrid (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2024).

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. The Ambiguous Allure of the West: Traces of the Colonial in Thailand, eds. y Rachel V. Harrison and Peter A. Jackson. (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010).

- Townsend, Rebecca. Cold Fire: Gender, Development, and the Film Industry in Cold War Thailand In History. Vol. PhD. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 2017.

- ประสาทไทย ช. “Reading Thai Society and Politics through Zombies in Thai Films and other Media,”Social Sciences Academic Journal 28 (2):105-31.

- Champion, Giulia , Roxanne Douglas , and Stephen Shapiro, ed. Decolonizing the Undead: Rethinking Zombies in World-Literature, Film, and Media (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023).

- MEMORIA. Festival international de Cinéma Marseille - FIDMarseille [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024-05-09]. Available from: https://www.thairath.co.th/agr.... https://fidmarseille.org/en/fi...;