PROTODISPATCH

A monthly digital publication of artists’ dispatches on the life conditions that necessitate their work.

FEBRUARY 15, 2023

FEBRUARY 15, 2023

AIDING AND ABETTING IRAN’S WOMEN’S REVOLUTION

How a group of transnational artists are using archiving and accelerated storytelling as radical acts of resistance.

Homa and Saba*

Türkçe versiyonu için lütfen aşağı kaydırın.

Image captions from left to right: 1- Image of Jina “Mahsa” Amini’s grave. 2- A vigorous scene of protesters in Bukan. 3- Petals in the palm of a hand with the text: “Woman, Life, Freedom” (in Kurdish and Persian) added to the image.

I was that image, I was coming to my senses and realizing that I am in a ring of women burning headscarves as if I had always been doing that before. I was coming to my senses and realizing I was being beaten a few moments ago (1).

The circulation of information has been a key concern in Iran's ongoing uprising/revolution, which started on September 16, 2022 following the killing of Jina “Mahsa” Amini at the hands of the Islamic Republic’s morality police. With the suppression of local journalists and the absence of foreign reporters, documentation of the uprising has come from civilians, who send and share daily raw footage and photos via social media accounts of varying organizations, serving as the primary sources of news. This system of sharing from Iran to the outside world has been ongoing for four months despite persistent internet blackouts by the state to control the spread of information related to its violent crackdown. While it appears that major Western media organizations have been slow or unwilling to adapt their reporting to Iran's current context and that regional outlets have purposefully silenced the spread of this information for fear of the consequences on their own stability, individuals from Iran and the diaspora have been using posts and stories on their personal social media accounts to share news and to create context for their networks.

The perpetual sharing and resharing of updates over social media, with all the truths and inaccuracies that it entails, is further characterized by frequent and necessary erasures of the original content creator's identity to protect them from government security forces. Participating in any aspect of social media that acts in support of the current protests can be cause for arrest by the Iranian regime. It has become commonplace for many locals to purge their phones daily and erase their social media archives as a safety measure. Following widespread and indiscriminate arrests of protesters—everyone from celebrities and athletes to workers, activists, and students all across the country—the regime has made it clear that no one will be spared from their wrath. They have been especially ruthless in their retaliations against Kurdish and Baluch communities, as well as other ethnic and religious minorities and queer communities. Nonetheless, this has not dissuaded a growing number of public figures from using their large platforms to support the uprising. Protestors have been channeling their growing rage by demanding the release and pardoning of political prisoners, calling for boycotts of brands associated with the regime, and, more importantly, using digital as well as analog means to call for three-day nationwide strikes at increasingly frequent intervals.

Just as oral traditions in the past played a pivotal role in the transmission and preservation of culture and information from generation to generation, we similarly see the current phenomenon as a kind of accelerated oral practice of the digital age.

With declining adult attention spans—thanks, in part, to the burgeoning use of social media—the stakes have never been higher for a cause to go viral in order to make headlines and inform the world. But beyond amplifying stories of resistance from Iran, we see this incessant and ubiquitous sharing as part of a conscious insistence on remembering and a refusal to succumb to collective amnesia. It is an active stance against the erasure of crimes committed by those in power, to record the names and identities of those killed, and to recall the constellation of views that currently exist in opposition to the political landscape, both within Iran and across the diaspora. It reflects an awakening of Iranians within Iran who had been forced into numbness in order to survive and who have stayed silent for fears of the harshest backlash that could otherwise await them. It is as though we have arrived at the end of a cycle within our society: the unyielding facade of the Islamic Republic and the narratives it has imposed on the public since its founding are being brazenly shattered from below, by hundreds of thousands of individuals insisting on disseminating their own accounts and truths.

* * *

This exercise in collective archiving is a response to and a way to process the flood of daily videos, images, and slogans that are being shared about Iran and that disappear each day due to the nature of Instagram’s twenty-four-hour stories and content algorithm. We are a collective of women from Iran who are gathering images of social media posts from various accounts in an effort to create a collective archive of this developing popular uprising. The impetus to create and share content about the uprising can be a solitary act of survival that echoes an unceasing rage and desire to take some form of action to ensure the remembrance of these brave acts. In turn, the sharing and circulation of news and commentaries garners an ever-growing and insatiable viewership seeking answers and hope, despite the absence of any promised resolutions. Anger is a healthy and legitimate response by the people and we recognize its importance and its role in the drive for change. Perhaps this channeling of collective wrath on virtual platforms is also a way that physical violence on the ground can be prevented or sustained to a lesser degree. We understand that the current fury towards the government, its supporters, and its agents (religious clerics, for example, or the children of corrupt officials who live lavishly abroad) is wholly justified, yet by no means do we support retaliation in the form of further violence. We stand for holding accountable agents of the regime in courts of law.

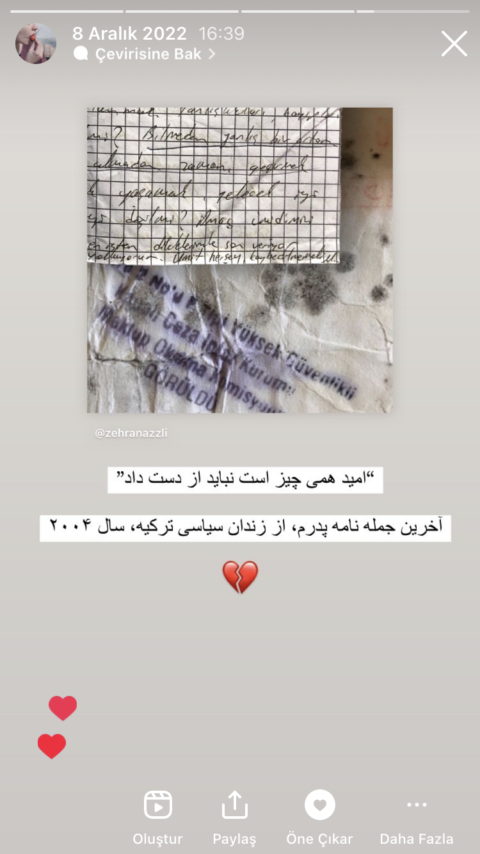

For the first iteration of this project, we have limited the collected archives to content gathered from the social media accounts of five individuals chosen for factors such as their location, perspective, and breadth of content creation. They include: Bahar, Goli, Mitra, Sheen, and Zehra (2). The screenshots, collected through the end of 2022, consist of both posts created by these individuals, as well as content that has been saved and shared by others, reflecting a variety of views and stories, as well as a way to maintain the privacy of those who wish to remain anonymous (3).

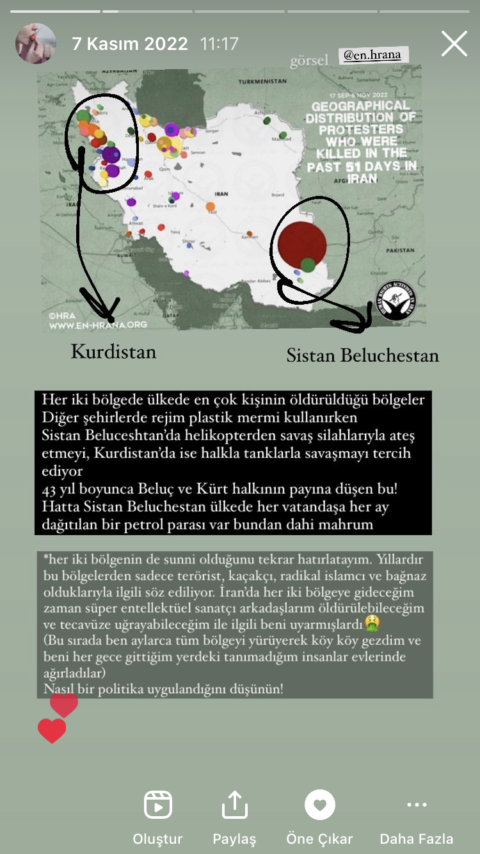

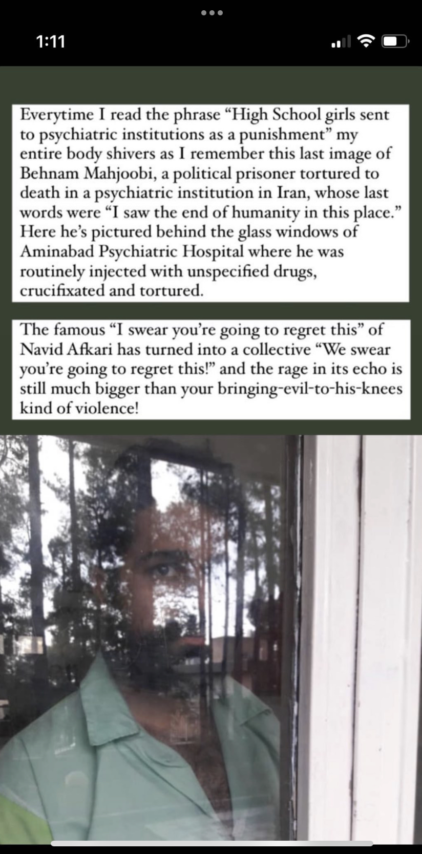

In this initial collection of social media content, we contextualize aspects of the protests by highlighting emerging tropes that we believe are important to call attention to at this time. These include: Solidarity/Transnational Movements, Intimidation/Systemic Oppression, Mourning, and Code-Making. We acknowledge that this endeavor does not and cannot address an all-encompassing scope of the current and evolving situation in Iran, Kurdistan, and the broader region. A multitude of facets of resistance is also reflected from within each of the four groupings, such as images of unyielding courage in the face of bloodshed, still frames of gestures in reference to the uprising publicly performed by athletes and other celebrities, and photos of women without headscarves walking or eating in public across different cities. Many of these images can be placed in multiple groups, and once we arrive at the Code-Making category, we see the merging of the themes. While the images may at times feel disconnected, particularly for a reader unfamiliar with Iran’s political climate, histories, and current organizing, we hope the archive will encourage readers to further delve into the nuances and stakes of this protracted revolution. The skewed image that people around the world have of Iran is often filtered through geopolitical journalism or Hollywood. Is it any surprise, then, that Iranians are potentially risking their lives in order to disseminate information about events unfolding on the ground? As we write, social media pressure from both locals and the diaspora is being used specifically to try and save the protesters who have been sentenced to death: virtual platforms as a means to preserve physical bodies. This women-led revolution is fundamentally about the body, bodies of women, queer and minority communities, and their rights to exist. Because freedom is conceived in the mind, but it is lived in the body.

* * *

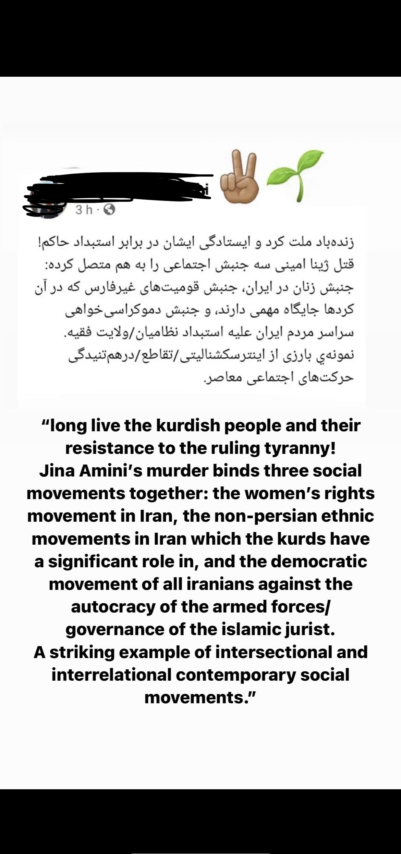

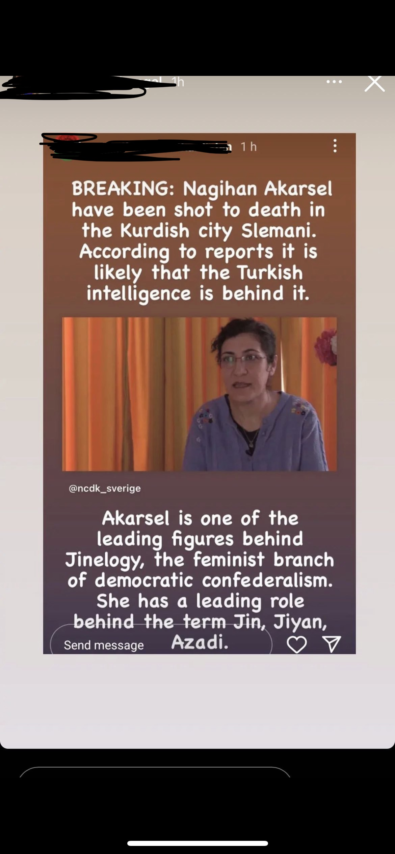

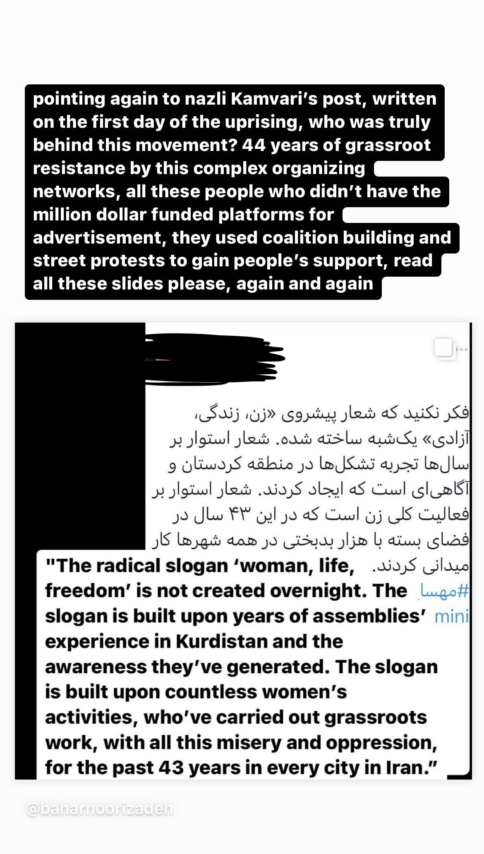

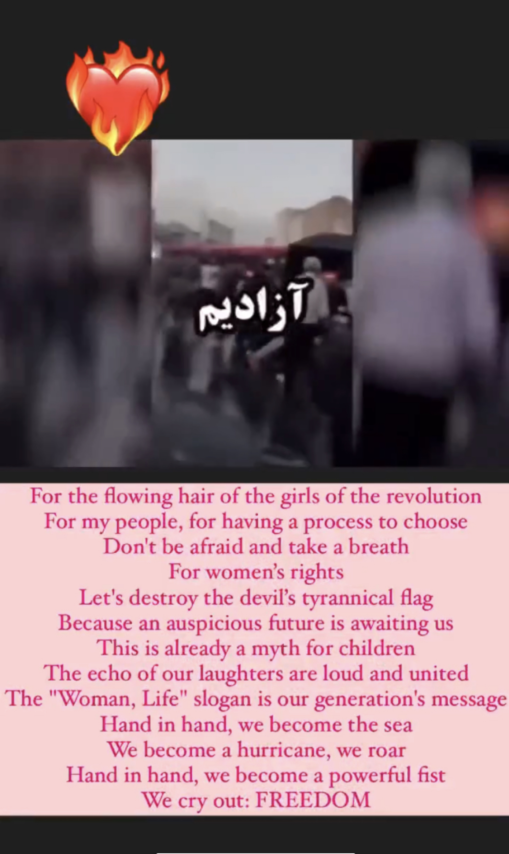

Solidarity/Transnational Movements

At Jina “Mahsa” Amini’s funeral, women from her hometown of Saqqes in Rojhelat (Eastern Kurdistan/Northwest Iran) were recorded removing their headscarves and chanting: Jin, Jiyan, Azadi (Women, Life, Freedom). This Kurdish slogan has been translated into Persian, (Zan, Zendegi, Azadi), among other languages spoken across Iran, and has since been recognized as one of the main pillars of this uprising. Its origin can be traced back to decades-long Kurdish armed and civil opposition against the Turkish state. Within this movement, women’s liberation continues to be a driving force toward achieving democracy and autonomy.

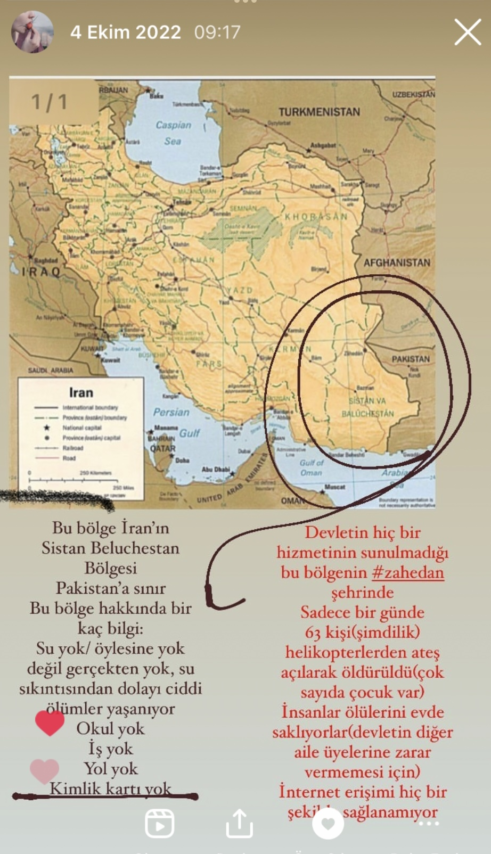

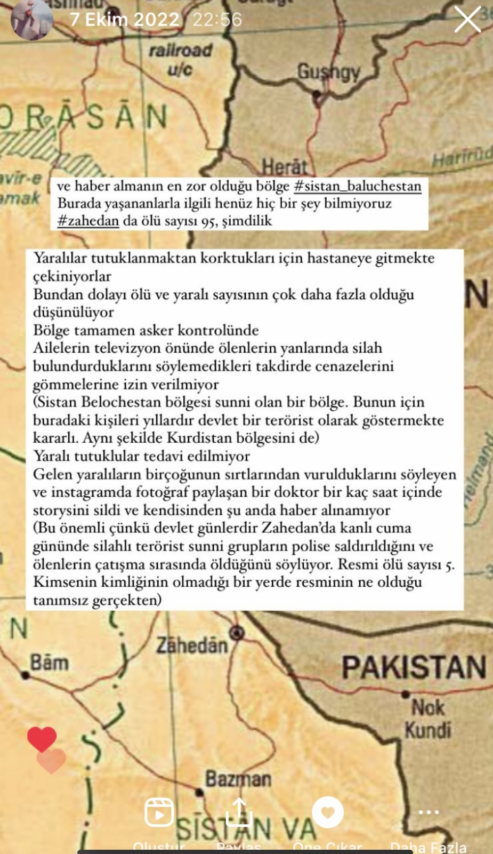

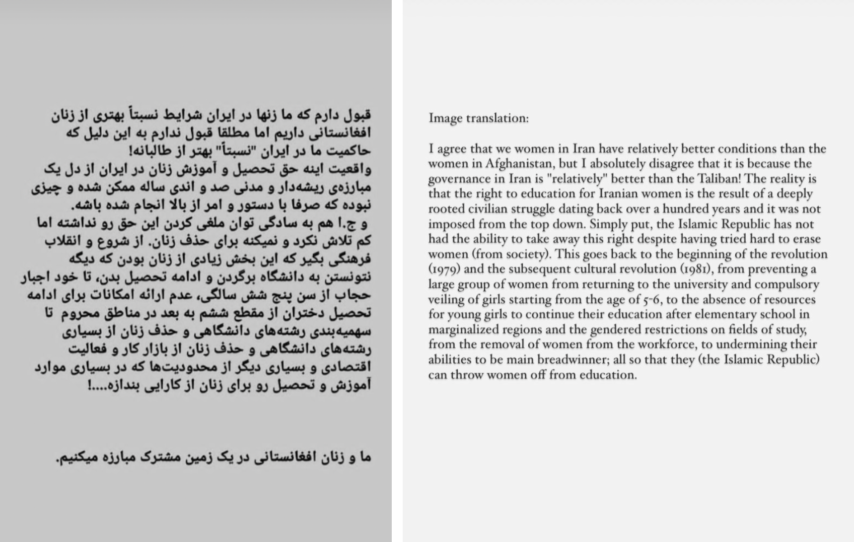

Transnational solidarity and intersectional protest movements have played a role in framing the resistance since the start of Iran’s uprising. This series of photos reflects the efforts of many on social media to center Kurdish and Baluch women and their respective communities, to center their longstanding struggles against the oppressive central government in Tehran. If communities on the ground are finding ways to support each other beyond borders and across countries, nation-states have, in turn, been using force to maintain these frontiers and silence critical voices, further fueling the people’s drive to resist. Women in Afghanistan, who have themselves been steadily losing rights since the Taliban takeover in 2021, have raised their voices in solidarity with Iranian women.

Protesters throughout the region and in the Global South are learning from each other and borrowing songs, slogans, and methodologies of resistance.

The struggles of all peoples against their dictatorial and nationalist regimes are interconnected. The liberation of Iranian women and minority communities within Iran will have direct consequences on communities in neighboring Turkey, Afghanistan, Kurdistan, Iraq, and the region as a whole.

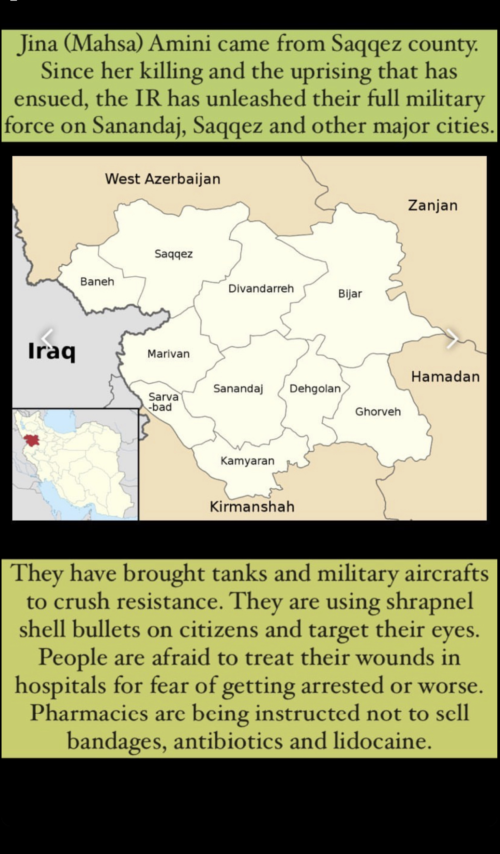

Intimidation/Systemic Oppression

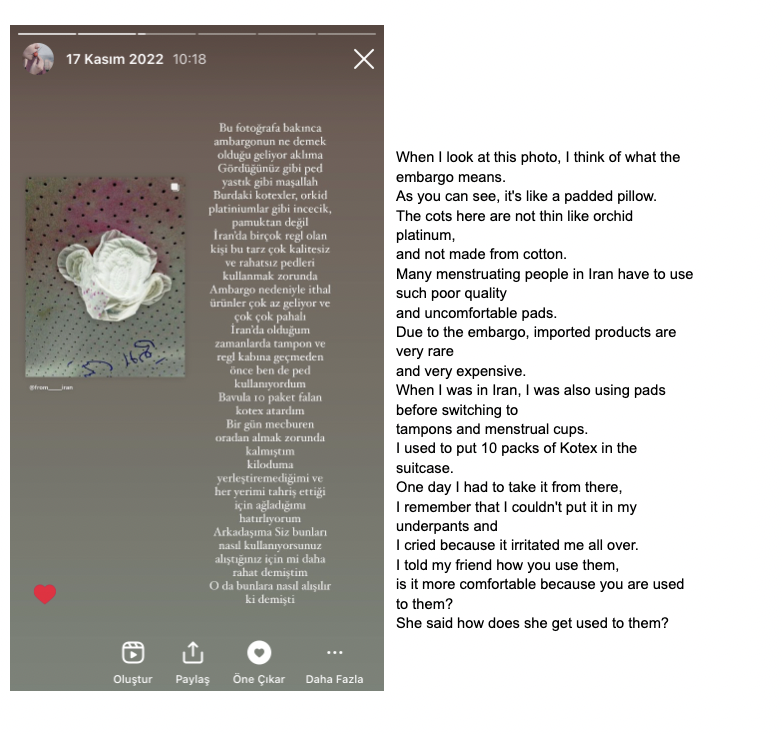

Since taking power forty-four years ago, in 1979, the Islamic Republic has used terror and force to silence its opponents and to deter others from challenging its rule. To crush the current uprising, the regime has not hesitated to display its familiar draconian methods of oppression and intimidation which include internet outages, threats, shutting down businesses, spying, wide-scale arrests, forced confessions, sham trials, physical and white torture, the rape of prisoners, executions, among many others.

This selection of photos includes accounts of those who have suffered at the hands of the regime as well as references to past uprisings and resistance movements. What is conveyed is the protestors' and activists’ unfaltering will to persevere despite systemic assaults against their resolve. While the struggle of activists, writers, thinkers, as well as union and community organizers, may not make international headlines, these groups have been active for decades despite life-threatening conditions.

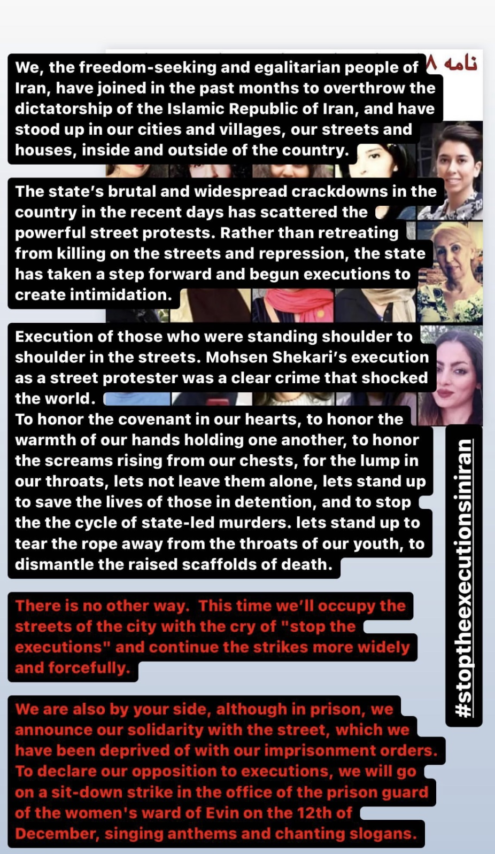

Mourning

The tradition of grieving one’s loved ones plays a significant role in Iranian society. The mourning period lasts forty days; the third, seventh, and fortieth days after a person dies mark the most important days of commemoration. With the government’s ongoing killing spree, they have unleashed a continuous chain of mourning-gatherings that develop into massive community-wide protests against unjust murders. These images offer only a glimpse into the scope of deaths and horror to which communities across Iran have borne witness.

Mourning traditions linked to Shiism have been embedded within the Iranian psyche thanks to the Iranian regime’s commandeering of the faith, however, other forms of grieving have become visible and some are even emerging without prior legacy. People across Iran are learning about forms of mourning practiced by ethnic communities that have existed on the margins of the mainstream. We are witnessing a different kind of collective mourning that includes dancing, celebrating the birthdays of killed protesters, and freeing birds at the graves of the deceased. There is a collective mobilization and recognition that has been born from mourning, and the regime no longer holds the authority to ratify or discredit forms of grief.

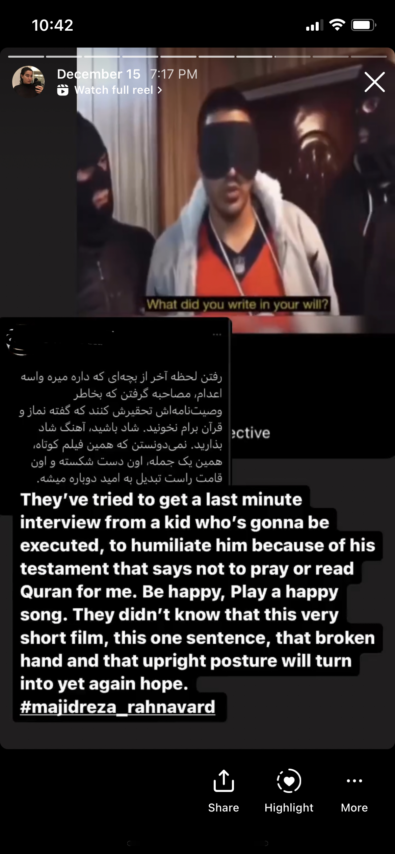

On November 3rd, 2022, during the fortieth-day commemoration of Hadis Najafi, a young woman killed by security forces in Karaj, hundreds of people were arrested. The regime has arbitrarily pinned the death of a paramilitary officer on sixteen protesters from that night and, at the time of writing, four men have been executed: Mohsen Shekari, Majidreza Rahnavard, Mohammad Mehdi Karami, and Mohammad Hosseini. Although executions have occurred throughout the Islamic Republic's forty-four-year reign, the collective public outrage against capital punishment has erupted across Iran on a scale not seen before.

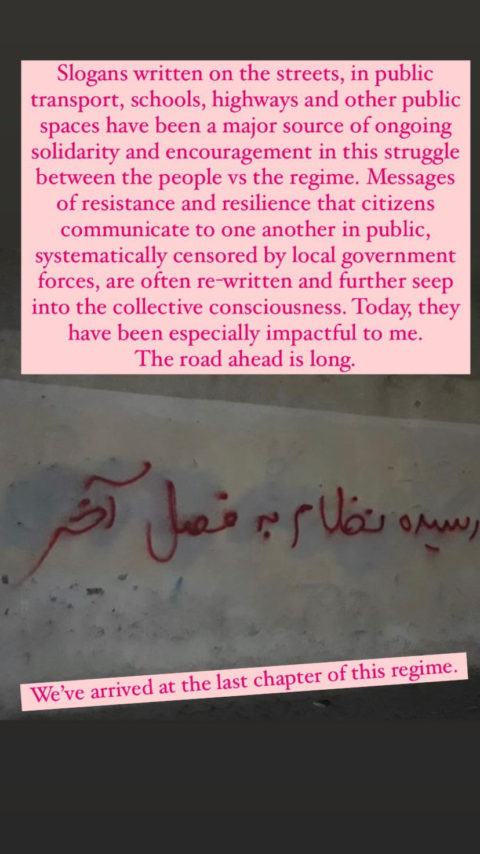

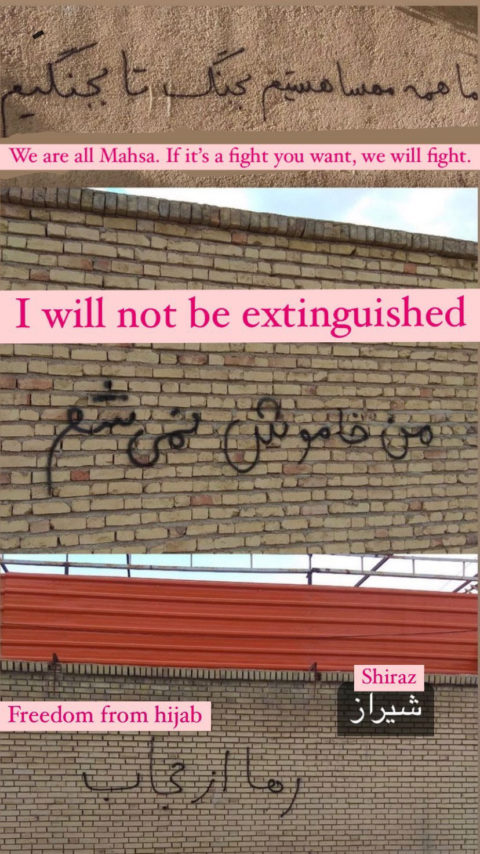

Code-Making

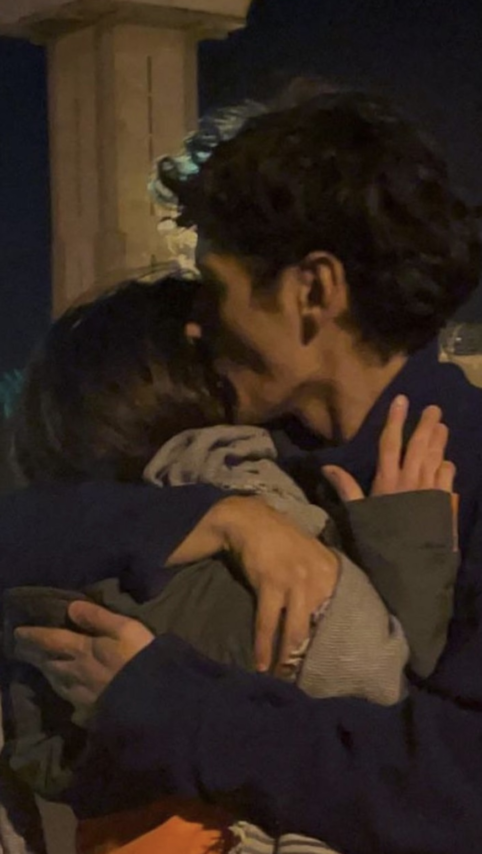

With each day that the revolutionary uprising in Iran perseveres, codes of resistance continue to emerge; they are as identifiable on the streets as they are on social media. The final grouping of images brings together symbols and codes of this revolution, such as spray painted slogans in cities across Iran, locks of hair cut off by women in protest, women in public without headscarves, queer love, embracing in public, the composing of new revolutionary songs, and many more. Jina’s name, with its roots in the Kurdish word Jiyan (Life), is perhaps the most prominent of these new codes.

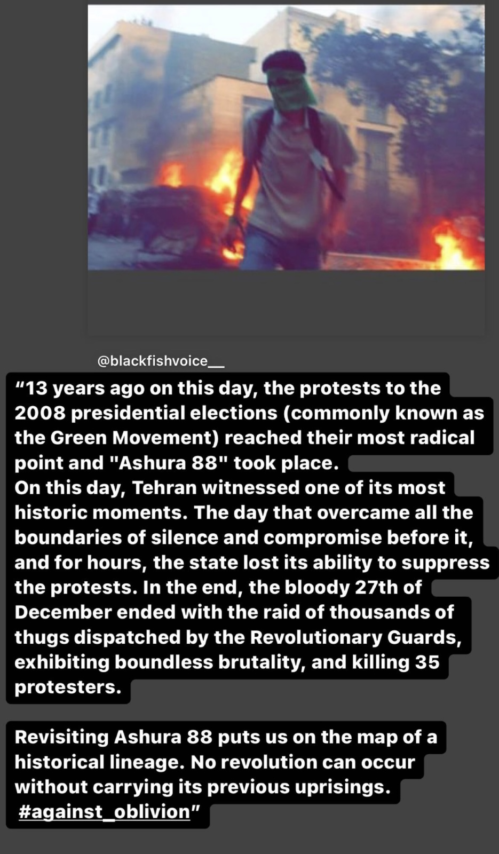

Fire is a means by which protestors have been purging cities of the regime’s symbols and propaganda. People have been jumping on trash cans to lead chants and setting them on fire, which has become one of the only means for unarmed protesters on the ground to protect themselves from the security forces’ bullets. In this uprising, fire has been used to destroy, protect, and create spaces for renewal.

The codes that emerge on the ground are circulated online in the form of videos, photographs, and slogans. While regime forces exert violence to censor these codes in the physical realm, they are unable to stop their spread virtually. Content uploaded to the internet and to social media platforms is permanent, yet concurrently there is an inevitable erasure of the content producer’s identity once the code begins to take on a new digital life. The symbols and imagery of this women’s revolution are becoming codified in the virtual records of history. Today, “woman” is intrinsically linked to the body and synonymous with “freedom.” To live in Iran, to express joy, to feel love, are all continual acts of defiant resistance against an oppressive, corrupt system. These new codes give root to collective hope and further enable us to envision the end of this regime.

WOMAN, LIFE, FREEDOM

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* Homa and Saba are pseudonyms to preserve the writers’ identities.

1- L, “Women Reflected in Their Own History,” e-flux Notes, October 14, 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/notes/497512/women-reflected-in-their-own-history, last accessed Jan 8, 2023.

We highly recommend this text in which the anonymous writer L so aptly describes her experiences protesting from her town. Her descriptions and recollections create a tangible imaginary of this revolution and its potential to be realized. We admire L’s approach to language in its inherent visuality and, in turn, our text is born out of archives of visuals.

2- Some names have been changed to protect individuals’ identities.

3- Bahar is an artist, writer, and filmmaker based in London. She has been translating and contextualizing content for English-speaking audiences. Goli is an artist working out of Los Angeles and focusing on the aesthetics of mourning. Mitra is a writer based in Toronto, researching subcultures within the Iranian diaspora. Living in Tehran, Sheen is an artist who has steadily gained an audience with whom she engages in dialogues based on her reflections and critical questioning. Zehra, who is currently based in Istanbul, lived in Iran as an artist for eight years and has been translating posts and current news from the uprising into her native Turkish.

İran kadın devrimine yardım ve yataklık

Bir grup ulusötesi sanatçı arşivlemeyi ve dijital hikâye anlatımını radikal direniş eylemleri olarak nasıl kullanıyor?

Ben o görüntüydüm, kendime geliyordum ve sanki daha önce hep böyle yapıyormuşum gibi, başörtüsü yakan bir kadın grubunun içinde olduğumu fark ediyordum. Tekrar kendime geliyordum ve birkaç dakika önce dövüldüğümü fark ediyordum.[1]

16 Eylül 2022’de Jina “Mahsa” Amini’nin İslam Cumhuriyeti’nin ahlak polisi tarafından öldürülmesinin ardından başlayan İran’ın devam eden ayaklanmasına/devrimine dair bilgilerin dolaşıma sokulması önemli bir endişe kaynağı oldu. Yerel gazetecilerin baskı altında olması ve yabancı muhabirlerin yokluğu sebebiyle, ayaklanmanın belgeleri, birincil haber kaynağı olarak çeşitli kuruluşların sosyal medya hesapları aracılığıyla günlük ham görüntü ve fotoğraflar gönderip paylaşan sivillerden geldi. İran’dan dış dünyaya yapılan bu paylaşım sistemi, şiddetli baskısıyla ilgili bilgilerin yayılmasını kontrol etmek isteyen devletin sürekli internet kesintilerine rağmen dört aydır devam ediyor. Batılı büyük medya kuruluşlarının haberlerini İran’ın mevcut bağlamına adapte etme konusunda yavaş veya isteksiz davrandığı ve bölgesel yayın organlarının kendilerinin istikrarı üzerindeki sonuçlarından korktukları için bu bilgilerin yayılmasını kasıtlı olarak susturdukları görülse de İran’daki ve diasporadaki insanlar haberleri paylaşmak ve kendi ağları için kaynak oluşturmak amacıyla kişisel sosyal medya hesaplarındaki gönderileri ve hikâyeleri kullanıyor.

Güncellemeler içerdiği tüm hakikatler ve yanlışlıklarla birlikte sosyal medya üzerinden sürekli olarak önce paylaşılıp ardından siliniyor ve daha sonra yeniden paylaşılıyor. Orijinal içerik oluşturucusunun kimliğini devlet güvenlik güçlerinden korumak için gerekli görülen bu silme işlemi sık sık uygulanan bir önlem. Mevcut protestoları desteklemek amacıyla hareket eden bu sosyal medya paylaşımlarına herhangi bir şekilde katkı sunmak, İran rejimi tarafından tutuklanma sebebi sayılabiliyor. Bu nedenle İran’da yaşayan pek çok insan için güvenlik önlemi almak amacıyla telefonlarını günlük olarak temizlemek ve sosyal medya arşivlerini silmek artık sıradan bir durum haline geldi. Ülke çapında ünlülerden sporculara, işçilerden aktivistlere ve öğrencilere kadar protestocuların yaygın bir şekilde ve ayrım gözetmeksizin tutuklanmaya başlamasıyla birlikte İran yönetimi hiç kimsenin rejimin gazabından kurtulamayacağını açıkça ortaya koymuş oldu. Kürt ve Beluç topluluklarının yanı sıra diğer etnik ve dini azınlıklar ve queer topluluklara karşı yapmış oldukları misillemelerde özellikle acımasız davrandılar. Yine de bu durum, sayıları her geçen gün artan kamuya mal olmuş kişilerin bu tür platformları ayaklanmayı desteklemek için kullanmaktan caydırmadı. Protestocular, siyasi tutukluların serbest bırakılmasını ve affedilmesini, rejimle bağlantılı markaların boykot edilmesini talep ederek ve daha da önemlisi dijital ve analog araçları kullanarak ülke çapında giderek daha sık aralıklarla uygulanan üç günlük grev yapma çağrısında bulunarak her geçen gün artmakta olan öfkelerini eyleme döküyorlar.

Tıpkı geçmişteki sözlü geleneklerin, kültür ve bilginin nesilden nesile aktarılmasında ve korunmasında önemli bir rol oynaması gibi, biz de benzer şekilde günümüzün bu olgusunu dijital çağın bir tür hızlandırılmış sözlü uygulaması olarak görüyoruz. Kısmen sosyal medyanın artan kullanımına bağlı olarak yetişkinlerin azalan dikkat süreleri nedeniyle manşetlere çıkmak ve dünyayı bilgilendirmek için bir olayın viral hale gelmesi için riskler hiç bu kadar yüksek olmamıştı. Ancak İran’dan gelen direniş hikâyelerini güçlendirmenin ötesinde, biz bu sürekli devam eden ve her yerde bulunan paylaşımları, hatırlama konusunda bilinçli bir ısrarın ve toplu belleksizliğe yenik düşmeyi reddetmenin bir parçası olarak görüyoruz. Böylesi bir tavır, iktidardakilerin işlediği suçların örtbas edilmemesine, öldürülenlerin isimlerinin ve kimliklerinin kayıt altına alınmasına ve hem İran’daki hem de diaspora genelindeki siyasi manzaraya karşı şu anda var olan görüşlerin hatırlanmasına yönelik etkin bir duruştur. Bu duruş, İran’da hayatta kalabilmek için tepkisiz kalmaya mecbur bırakılan, aksi takdirde başlarına gelebilecek en sert tepkiden korktuğu için sessiz kalan İranlıların uyanışını yansıtıyor. Sanki toplumumuzdaki bir döngünün sonuna gelmiş gibiyiz: İslam Cumhuriyeti’nin boyun eğmez cephesi ve kuruluşundan bu yana halka dayattığı anlatılar, kendi değerlerini ve gerçeklerini yaymakta ısrar eden yüz binlerce kişi tarafından cesurca en temelinden yıkılıyor.

***

Bu kolektif arşivleme uğraşı, İran hakkında paylaşılan ve Instagram’ın yirmi dört saatlik hikâyelerinin ve içerik algoritmasının doğası gereği her gün kaybolan günlük video, resim ve slogan akışlarının işleyişine dair bir tepki ve alternatif oluşturmaya çalışmaktadır. Biz büyümekte olan bu halk ayaklanmasının kolektif bir arşivini oluşturmak amacıyla çeşitli hesaplardan sosyal medya paylaşımlarının görüntülerini toplayan İranlı kadınlardan oluşan bir kolektifiz. Ayaklanma hakkında içerik oluşturma ve paylaşma dürtüsü, bu cesur eylemlerin hatırlanmasını sağlamak için bir tür eylemde bulunma arzusunu ve dinmeyen bir öfkeyi yansıtan münferit bir hayatta kalma eylemi gibi görülebilir. Öte yandan, haberlerin ve yorumların paylaşılması ve dolaşımı, vaat edilen herhangi bir çözüm olmamasına rağmen, cevaplar ve umut arayan, sürekli büyüyen ve doymak bilmeyen bir izleyici topluyor. Öfke, insanlar tarafından sağlıklı ve meşru bir tepkidir ve öfkenin değişim dürtüsü oluşturmasındaki önemini ve rolünü kabul etmekteyiz. Belki de bu toplu hıncın sanal platformlara yönlendirilmesi, aynı zamanda sahadaki fiziksel şiddetin önlenmesinin veya daha az olmasının bir yolu olabilir. Bizler hükümete, destekçilerine ve temsilcilerine (örneğin din adamlarına veya yurtdışında cömertçe yaşayan yozlaşmış yetkililerin çocuklarına) yönelik mevcut öfkenin tamamen haklı olduğunu anlıyoruz, ancak daha fazla şiddet oluşturabilecek misillemeleri hiç bir şekilde desteklemiyoruz. Rejimin temsilcilerinin mahkemelerde hesap vermesi gerektiğini savunuyoruz.

Projenin ilk ayağında, toplanan arşivleri, konumları, bakış açıları ve içerik oluşturma çeşitlilikleri gibi faktörler neticesinde seçilen beş kişinin sosyal medya hesaplarından toplanan içerikle sınırlandırdık. Bu kişiler: Bahar, Goli, Mitra, Sheen ve Zehra.[2] 2022’nin sonuna kadar toplanan ekran görüntüleri, hem bu kişiler tarafından oluşturulan gönderilerden hem de başkaları tarafından kaydedilen ve paylaşılan çeşitli görüş ve hikâyeleri yansıtan içeriklerden oluşuyor ve de anonim kalmak isteyenlerin gizliliğinin korunmasını sağlıyor.[3]

Bu ilk sosyal medya içeriği koleksiyonunda, mevcut durum açısından dikkat çekmenin önemli olduğuna inandığımız temaları vurgulayarak protestoların çeşitli yönlerine dair bağlam oluşturuyoruz. Bu temalar şöyle: Dayanışma / Ulusötesi Hareketler, Sindirme / Sistemik Baskı, Yas Tutma ve Kod Oluşturma. Bu çabanın İran, Kürdistan ve daha geniş bölgedeki mevcut ve gelişen durumun tüm unsurlarını içeren bir kapsamı ele almadığının ve alamayacağının farkındayız. Dört grubun her birine dair, öldürülme pahasına boyun eğmeyen cesaret görüntüleri, sporcular ve diğer ünlüler tarafından halka açık bir şekilde gerçekleştirilen ayaklanmaya atıfta bulunan kareler ve farklı şehirlerde halka açık yerlerde baş örtüsü olmadan yürüyen veya yemek yiyen kadınların fotoğrafları gibi çok sayıda direniş yönü de yansıtılmaktadır. Bu görüntülerin birçoğu birden fazla gruba yerleştirilebilir ve Kod Oluşturma kategorisine geldiğimizde tüm temaların birleştirildiğini görebiliriz. Bu görüntüler, özellikle İran’ın siyasi iklimi, tarihi ve mevcut örgütlenmesine aşina olmayan bir okuyucu için zaman zaman bağlantısız gibi görünse de, biz bu arşivin okuyucularını bu uzun süreli devrimin nüanslarını ve risklerini daha fazla araştırmaya teşvik edeceğini umuyoruz. Dünyanın dört bir yanındaki insanların İran hakkında sahip olduğu çarpık imaj, genellikle jeopolitik gazeteciliğin veya Hollywood’un filtrelerinden doğru oluşuyor. Durum böyleyken, İranlıların sahada meydana gelen olaylar hakkında bilgi yaymak için potansiyel olarak hayatlarını riske atmaları şaşırtıcı mı? Daha önce de belirttiğimiz gibi, hem yerel halktan hem de diasporadan gelen sosyal medya baskısı, özellikle ölüm cezasına çarptırılan protestocuları kurtarmak için kullanılıyor, sanal platformlar bedenlerinin fiziksel bütünlüğünü korumanın bir aracı haline geliyor. Kadınların önderlik ettiği bu devrim temelde beden, kadınların, queerlerin ve azınlıkların bedenleri ve bu toplulukların var olma haklarıyla ilgilidir. Çünkü özgürlük zihinde tasavvur edilir, ama bedende yaşanır.

Dayanışma / Ulusötesi hareketler

Jina “Mahsa” Amini’nin cenazesinde, memleketi Rojhelat, Saqqes’teki (Doğu Kürdistan/Kuzeybatı İran) kadınların başörtülerini çıkardıkları ve Jin, Jiyan, Azadi (Kadın, Yaşam, Özgürlük) sloganları attıkları kaydedildi. Bu Kürtçe slogan, İran genelinde konuşulan diğer dillerin yanı sıra Farsça’ya çevrildi (Zan, Zendegi ,Azadi), ve o zamandan beri bu ayaklanmanın temel dayanaklarından biri olarak kabul edildi. Kökeninin, Türk devletine karşı onlarca yıldır süren Kürt silahlı ve sivil hareketine kadar uzandığı görülebilir. Bu hareket içinde kadınların kurtuluşu, demokrasiye ve özerkliğe ulaşma yolunda itici bir güç olmaya devam ediyor.

Ulusötesi dayanışma ve kesişimsel protesto hareketleri, İran ayaklanmasının başlamasından bu yana direnişin çerçevesinin belirlenmesinde önemli bir rol oynadı. Bu fotoğraf dizisi, sosyal medyadaki pek çok kişinin Kürt ve Beluç kadınlarını ve kendi toplumlarını merkeze alma, Tahran’daki baskıcı merkezi hükümete karşı uzun süredir devam eden mücadelelerini merkez alma çabalarını yansıtıyor. Sahadaki topluluklar birbirlerini sınırların ötesinde ve ülkeler arasında desteklemenin yollarını buldukça, ulus devletler de bu sınırları korumak ve eleştirel sesleri susturmak için güç kullanıyorlar ve bu şekilde halkın direnme dürtüsünü daha da körüklemiş oluyorlar. Örneğin Taliban’ın 2021’de devralmasından bu yana haklarını sürekli kaybeden Afganistan’daki kadınlar, İranlı kadınlarla dayanışma içinde seslerini yükselttiler.

Bölgedeki ve Küresel Güney’deki protestocular birbirlerinden öğreniyorlar ve birbirlerinin şarkılarını, sloganlarını ve direniş yöntemlerini ödünç alıyorlar.Bütün halkların diktatörlük ve milliyetçi rejimlerine karşı mücadeleleri birbirine bağlıdır. İranlı kadınların ve İran içindeki azınlık topluluklarının kurtuluşunun, komşu Türkiye, Afganistan, Kürdistan, Irak ve bir bütün olarak bölgedeki topluluklar üzerinde doğrudan sonuçları olacaktır.

Sindirme / Sistemik baskı

İslam Cumhuriyeti, kırk dört yıl önce, 1979’da iktidara geldiğinden beri, muhaliflerini susturmak ve yönetimlerine meydan okumak isteyenleri caydırmak için daima terör yarattı ve güç kullandı. Mevcut ayaklanmayı bastırmak için rejim, hepimizin aşina olduğu internet kesintileri, tehditler, işletmeleri kapatma, casusluk, geniş çaplı tutuklamalar, zorla itiraflar, sahte yargılamalar, fiziksel ve beyaz işkence mahkumlara tecavüz, infazlar ve başka bir çok benzeri şeyi içeren çeşitli zalimane baskı ve sindirme yöntemlerini sergilemekten çekinmedi.

Bu fotoğraf seçkisi, rejimin ellerinde baskı görenlerin anlatımlarının yanı sıra geçmişteki ayaklanmalara ve direniş hareketlerine atıfları da içeriyor. Protestocuların ve aktivistlerin gösterdikleri kararlılık karşısında maruz kaldıkları sistematik saldırılara rağmen sebat etme konusundaki sarsılmaz iradelerini aktarıyor. Aktivistlerin, yazarların, düşünürlerin, sendika ve topluluk örgütleyicilerinin mücadelesi uluslararası manşetlerde yer almasa da bu gruplar yaşamı tehdit eden koşullara rağmen onlarca yıldır aktif bir mücadele veriyorlar.

Yas tutma

İran toplumunda sevdiklerinin yasını tutma geleneği önemli bir rol oynamaktadır. Yas dönemi kırk gün sürer; bir kişinin ölümünden sonraki üçüncü, yedinci ve kırkıncı günler, en önemli anma günleridir. Hükümetin aralıksız devam eden öldürme çılgınlığı aynı zamanda haksız cinayetlere karşı toplum çapında kitlesel protestolara dönüşen sürekli bir yas toplantıları zincirini de başlatmış oldu. Bu görüntüler, İran’daki toplulukların tanık olduğu ölümlerin ve dehşetin kapsamına yalnızca kısa bir bakış sunuyor.

Şiilikle bağlantılı yas gelenekleri, İran rejiminin halkın inancını yönetmesi sayesinde İran ruhunun içine gömülmüştür, ancak farklı yas biçimleri de zaman içerisinde görünür hale geldi ve hatta bunların arasında daha önceki dönemlerden miras kalmamış olanlar da var. İran’daki insanlar, ana akım olmayan etnik toplulukların yas tutma biçimlerini öğreniyor. Dans etmeyi, öldürülen protestocuların doğum günlerini kutlamayı ve ölenlerin mezarlarında kuşları serbest bırakmayı içeren farklı bir toplu yas türüne tanık oluyoruz. Yastan doğan kolektif bir hareketlilik ve kabul var ve rejim artık yas biçimlerini onaylama veya itibarsızlaştırma yetkisine sahip değil.

3 Kasım 2022’de Karaj’da güvenlik güçleri tarafından öldürülen genç kadın Hadis Necefi’nin kırkıncı günü anmasında yüzlerce kişi tutuklandı. O geceden sonra Rejim gayet keyfi bir şekilde on altı protestocuyu bir paramiliter subayın ölümünden sorumlu tuttu ve bu yazının yazıldığı tarihte dört kişi idam edildi: Mohsen Shekari, Majidreza Rahnavard, Mohammad Mehdi Karami ve Mohammad Hosseini. İslam Cumhuriyeti’nin kırk dört yıllık hükümdarlığı boyunca çok sayıda infaz gerçekleşmiş olsa da, idam cezasına karşı halkın öfkesi İran genelinde daha önce görülmemiş bir ölçekte arttı.

Kod oluşturma

İran’daki devrimci ayaklanmanın devam ettiği her gün, direniş kodları ortaya çıkmaya devam ediyor; bu kodlar sosyal medyada olduğu kadar sokaklarda da doğuyor. Son gruptaki görüntüler, İran’ın dört bir yanındaki şehirlerde sprey boyalı sloganlar, protesto için kadınların kestiği saç telleri, başörtüsüz halkın arasında dolaşan kadınlar, queer aşk, toplu kucaklaşma eylemleri, yeni devrimci şarkılar bestelemek ve daha pek çok şey gibi bu devrimin sembollerini ve kodlarını bir araya getiriyor. Kökleri Kürtçe Jiyan (Yaşam) kelimesine dayanan Jina’nın adı, bu yeni kodların belki de en öne çıkanı.

Ateş ise protestocuların şehirleri rejimin sembollerinden ve propaganda araçlarından arındırdığı bir araç olmuş durumda. İnsanlar sloganlar atmak için çöp tenekelerine atlıyor ve onları ateşe veriyor, böylece hiç bir silahı olmayan protestocular kendilerini güvenlik güçlerinin kurşunlarından koruyorlar. Bu ayaklanmada ateş, yok etmek, korunmak ve yenilenme alanları yaratmak için kullanılan bir araç.

Ortaya çıkan bu kodlar videolar, fotoğraflar ve sloganlar şeklinde internette dolaşıyor. Rejim güçleri bu kodları fiziksel alanlarda sansürlemek için şiddet uygulasalar da yayılmalarını fiilen durduramıyorlar. İnternette dolaşan ve dolaşmaya devam eden görüntüler arasından bazılarının süregelen devrimin dışındaki kaynaklara dayandığı da görülebilir. Örneğin yaygın olarak paylaşılan ve güvenlik güçleriyle yaşanan çatışmaların ardından çekildiği sanılan kırık bir arabanın camından orta parmağını uzatan bir kadının görüntüsü aslında 2016 Lovers & Drifters Club moda çekiminden bir kare. Görüntülerin bu şekilde tahsis edilmesi kod oluşturmanın bir parçası haline geliyor ve söz konusu görseller bu tekrar tekrar paylaşılma sürecinde devrimle ilişkilendirilen yeni bir kimlik kazanıyorlar. İnternete ve sosyal medya platformlarına yüklenen içerik kalıcıdır, bununla birlikte bu kodlar yeni bir dijital hayata geçmeye başladığında, içerik üreticisinin kimliği de nihayetinde silinmiş oluyor. Bu kadın devriminin sembolleri ve imgeleri tarihin sanal kayıtlarında kodlanıyor. Günümüzde, “kadın” özü itibariyle bedenle bağlantılıdır ve aynı zamanda “özgürlük” ile eş anlamlıdır. İran’da yaşamak, sevinci ifade etmek, sevgiyi hissetmek, baskıcı, yozlaşmış bir sisteme karşı sürekli meydan okuyan direniş eylemleridir. Bu yeni kodlar kolektif umuda kök salmakta ve bu rejimin sonunu öngörmemizi daha da mümkün kılmaktadır.

KADINA, YAŞAMA, ÖZGÜRLÜĞE

İngilizceden çeviren: Erdem Gürsu

Protocinema’nın yeni dijital yayını PROTODISPATCH, sanatçıların kıtalararası kaygıları ele aldığı, kişisel bakış açılarını içeren deneme serilerinden oluşuyor. İngilizce dilinde yayınlanan denemeler Protocinema işbirliğiyle önümüzdeki yıl boyunca her ay Türkçe olarak Argonotlar’da kendine yer bularak bu küresel kaygıların Türkiye sanat ortamında da tartışılmasına alan açacak. Protodispatch’in diğer yayın partnerleri, New York’tan Artnet.com ve Bangkok’dan GroundControlth.com

*Homa ve Saba, yazarların kimliklerini korumak için kullanılan takma adlardır.

[1] L, “Women Reflected in Their Own History,” e-flux Notes, 14 Ekim 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/notes/497512/women-reflected-in-their-own-history, son erişim tarihi 8 Ocak 2023.

Anonim yazar L’nin kendi kasabasından protesto deneyimlerini gayet yerli yerinde anlattığı bu metni şiddetle tavsiye ediyoruz. Onun betimlemeleri ve hatıraları, bu devrimin somut bir tasavvurunu ve gerçekleştirilme potansiyelini ortaya koyuyor. L’nin dilin kendi içsel görselliğini de içinde barındıran yaklaşımına hayran kalıyoruz ama yine de bizim metnimizin doğması görsel arşivlere dayanıyor.

[2] Bireylerin kimliklerini korumak için bazı isimler değiştirildi.

[3] Bahar, Londra’da yaşayan bir sanatçı, yazar ve film yapımcısıdır. İngilizce konuşan izleyiciler için içerik çeviriyor ve bağlam oluşturuyor. Goli, Los Angeles’ta çalışan ve yas estetiğine odaklanan bir sanatçı. Mitra, İran diasporası içindeki alt kültürleri araştıran, Toronto’da yaşayan bir yazardır. Tahran’da yaşayan Sheen, kendi düşüncelerine ve eleştirel sorgulamalara dayalı diyaloglar kurduğu bir izleyici kitlesi olan bir sanatçı. Sekiz yıl İran’da yaşadıktan sonra şu an İstanbul’da çalışmalarına devam eden bir sanatçı olan Zehra ayaklanmadan gelen gönderileri ve güncel haberleri anadili olan Türkçesine çeviriyor.

https://argonotlar.com/iran-ka...