PROTOZINE

On the occasion of A Few In Many Places, Protocinema launches ProtoZine, comprised of five commissioned texts responding to each intervention from the viewpoint of another city. Taking place across five different cities in North America, Europe and Asia, the hyper-localized group exhibition is globally reconnected by way of this zine—both digitally and in-print—as every contributor responds to the commissioned art works.

A Few In Many Places is conceived with the curatorial intention that these exhibitions, regardless of the scale of audience, are experienced in real life, given the rapid push of digital life interactions. It offers a potential way to move forward, out of internet isolation, including ‘‘safe’’ exchange among our communities. The exhibition’s inclusive and pluralist vision takes this one step further as it allows visitors to learn from sibling interventions, going on simultaneously, and emphasizes a collective spirit. Functioning on a grassroots level—locally and across regions—it is deeply responsive to the unique contexts, in terms of time and place, that both the commissioned works and texts deal with.

Abbas Akhavan’s Spill and Untitled (2020) in Montreal; In Response written by Aslı Seven from Paris

Michelle Lopez’s Keep Their Heads Ringin’ (2020) in Philadelphia, In Response written by Abhijan Toto from Bangkok

Hasan Özgür Top’s The Fall of a Hero (2020) in Berlin; In Response written by Adam Kleinman from New York

Burak Delier’s Maya (2020) in Istanbul; In Response written by Fawz Kabra from New York

Stephanie Saade’s A Discreet Intruder (2020) in Beirut; In Response written by L. İpek Ulusoy Akgül from Istanbul

Download PDF of PROTOZINE here:

web / print

Logistics of the Living: Variations on a Crystal Case Text by Aslı Seven

They read Botanic Treatises,

And Works on Gardenin thro’ there,

And Methods of transplanting trees

To look as if they grew there.

[…]

They read in arbours clipt and cut,

And alleys, faded places,

By squares of tropic summer shut

And warm’d in crystal cases.

Alfred Tennyson, “Amphion”, 1842[1]

No discipline has influenced the fate of the colonial endeavor as much as botany in the 19th century. A hybrid fascination with the lush, tropical plant life and for the industrial and economic benefits of the newly discovered species drove not only the colonial settlers, administrators and scientists, but also members of the elite in metropoles to collect, study and display plant life from the colonies.

The global circulation of non-human living beings, however, was nonexistent, at least not until the 1830s. Transportation was by sea only. It took weeks or months for a ship to get to the ports of London, Bordeaux or Amsterdam. As almost 90% of the plants that were shipped from the colonies in Asia, Africa and America were dead by the time they arrived in Europe, botanists were appointed to these ‘‘floating gardens’’, as they were referred to at the time, to care for the plants, but to no avail. The solution came from an unlikely source in the form of a small glazed case that revolutionized the global colonial infrastructure.

Dr. Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward, who was a plant enthusiast, physician by profession, tried to grow fern and moths in his garden but failed at it due to the polluted London air in 1829. The accidental growth of moss and fern inside a sealed bottle where his moth cocoons were buried allowed Dr. Ward to observe “the moisture which, during the heat of the day arose from the mould, condensed on the surface of the glass, and returned whence it came; thus keeping the earth always in the same degree of humidity”[2]. Thus, the Wardian case, which allowed plant life to survive in autonomy inside a sealed box, was invented.

The so-called crystal case that could enclose and sustain “squares of tropic summer,” as Tennyson once wrote, defines a pivotal aesthetic regime within modernity and historically unleashes one of the most pervasive human actions on the planet at an unprecedented scale, namely the global trade and manipulation of plant life and interference in ecosystems. With it, the late 19th century saw an accelerated spread of invasive plant species in all directions, as plant acclimatization, industrial agriculture and bio-patenting turned out to be the vital forces sustaining European colonialism. The Wardian cases were the smallest and the most vital link in terms of the networks of exchange between the small-scale botanical stations in the colonies and the spectacular political and scientific powerhouses in Europe: Kew Gardens in London and, a bit later, Le Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale [The Garden of Tropical Agriculture] in Paris. These institutions lead the selection of industrially and economically profitable species of plants, and their distribution across the globe, in order to replace less viable species and establish vast zones of monoculture.

From a conceptual point of view, the object itself condenses two modernist imperatives in their apparent contradiction and fundamental entanglement still operative today: conservation and display. The Wardian case is at once an object, a space and a tool. It is not only an integral part of the colonial infrastructure with its portable size and protective design; it is also the ancestor of the present-day terrariums adorning our homes and our gentrified neighborhoods as commodities, and our schools as pedagogical tools. Moreover, it is a miniature greenhouse, a glass box of autonomous life on display, and a scheme for the accumulation of knowledge, capital and attention, all at the same time. As such, the Wardian case collects, displaces and isolates plant life, and serves as a display device that absorbs the gazes of the onlooker on its glazed surfaces.

Over time, the Wardian case diverged in design, as their functions evolved in two directions: logistics (transportation) and display (exhibition). Following the recommendations of Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle [The Museum of Natural History] in Paris, dating 1877, in its transportation function, the dimensions of the case needed to ideally be 100x50cm—height varying between 70-100cm. The base had to be elevated for protection from seawater. The upper part needed to have a frame to accommodate the glass, supported by wooden beams every 7 or 8cm. A wire fence had to cover the whole to shelter the glass against frequent impacts at the deck. Inside, the seedlings were planted, preferably in wicker pots to isolate them without breaking, within a careful layering of humid clayey soil that was followed by good quality soil mixed with compost. The soil was, then, covered with a bed of straws, which, in turn, was secured by wooden beams to prevent frequent tremors from affecting the plants[3]. In terms of protection, covers and layers, this design had diverged from the exhibitionary type of the Wardian case, which laid flat on the ground. Instead of solidity and insulation, it prioritized visibility.

The description above, of how to best secure a Wardian case, regardless of what it is that it carries, besides a utilitarian understanding of the category of “plants”, is a poignant example of life reduced to a method of governance. On a symbolic level, “life”, as an attribute, abandons the biologically living and its relational conditions of existence. The necropolitical capture of life in order to produce capital also curtails generative potentials not just in the biological realm, but also in the cultural and epistemological sense. Life primarily becomes a feature of the death-distributing infrastructure: growth of productive and reproductive networks, with accumulations of capital and cycles of returns on investment, surrounded by protective measures–material hardware, as in the Wardian cases, and software as in epistemic violence, insurance policies and catastrophe bonds.

There is a paradoxical relationship between what an unfolded Wardian case shelters and reveals, in line with its conservation-display function: the closed-off and wooden surfaced ones materially cover the plants as they reveal the colonial logistics of power, whereas the exhibitionary ones lay bare the display device in all its theatricality: procedures by which plant life is extracted, isolated and reduced to an image on a grid, as much as it reveals the gazes collected on its surfaces.

And what if we imagine it not only laid flat, but also pulled inside out: does it not look like a theatrical décor or a model house where plants become cut-out fragments? Could we interpret the case as a stage, and the plants as puppets?

When life is symbolically taken away from the living milieu and transferred to become a characteristic of human infrastructures of knowledge and capital, plants do seem like lifeless pieces that need human manipulation to be artificially inseminated, to breed, to travel and to sing a song.

There is, however, another way of looking at this. Humans do not process visual/spatial information without some form of identification. The mimetic bond goes in both ways, affecting the mime’s identity – or the puppet master’s: every time we manipulate a plant, in some tiny fragment of our consciousness, to a minor degree, we become one – or we think we do. Instead of holding on to the old and exhausted idea of autonomy and purity (be it of species, of knowledge categories or of artistic mediums), we could rewind and try to stay still for a minute in the midst of transition: between mask and persona; between the organism and its surroundings, between the ghost and the mime. Yes, the ultimate problem is, indeed, that of distinction: between the real and the imaginary, between waking and sleeping, between knowledge and ignorance, as literary critic Roger Caillois put it a long time ago[4]. But we could also explore the possibility that we have been—and still are—collectively suffering both from legendary psychasthenia and universal tropical neurasthenia[5].

[1] Lord Tennyson, Alfred. “Amphion”, 1842. http://www.public-domain-poetry.com/alfred-lord-tennyson/amphion-464. Last access 22 October 2020. [2] Ward, Nathaniel Bagshaw. On The Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases. London: John Van Voorst, originally published in 1852. https://archive.org/details/ongrowthplantsi00wardgoog. Accessed on 22 October 2020.

[3] Taken from “Caisses Ward”, Magasin Pittoresque. Paris, 1877, pp. 383-384. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k31460s/f388.item.planchecontact. Accessed on 22 October 2020.

[4] Legendary psychasthenia is used, here, as the disturbance of the relations between personality and space, as does Roger Caillois in “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia”, October (31), Winter 1984, MIT Press, pp. 16-32

[5] Universal Tropical Neurasthenia was a diagnosis in early 20th century colonial medicine, with symptoms ranging from exhaustion, amnesia, sun-pain, neurosis and suicide, affecting colonial settlers in tropical zones and thought to be an effect of tropical light. Anderson, Warwick. Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006

Aslı Seven is a curator and writer based between Istanbul and Paris. Her research and curatorial projects emphasize fieldwork, critical fiction and collaborative artistic processes with a focus on infrastructural forms of violence embodied within landscape and built environment.

That Which Is Not There

by Abhijan Toto

We talked to each other from the ends of the earth, connection shaky. There’s a storm outside. Our worlds are falling apart around us; we start talking immediately about the fires raging around us. I tell her about the student-led protests here in Bangkok, the Harry Potter-themed demonstrations as well as the clever and subversive use of popular culture, such as the three finger salute, adapted from the movie Hunger Games. She tells me about the mood of the Black Lives Matter movement, recent experiences of anti-Asian racism in the US. And of course, the man in the White House. Our talk quickly turns to the Philippines, a place we both have a relation of home to but both are, in a strange way, strangers to it, foreigners in a foreign way. The traces of the American withdrawal hold sway over the fortunes of this trice-colonized archipelago as the government of its current fascist sells the country piece by piece to the new regional super power. At the same time, he turns his attention to the censorship of the media, the murder of activists and passing of draconian legislation. The latest of these bears a curious trace of America’s legacy in the world - formulated as an “Anti-Terror Bill” by the government, and called simply as the “Terror Bill” by activists; it is the long unfolding of the ‘‘War On Terror’’ emerging from the American imperial imagination, where the ‘‘enemy’’ always remains the “unknown unknown”. A ghost, a shadow, always shapeshifting. That which is not there, but there. Activists warn of the use of the bill to ‘‘red-tag’’ anyone opposed to the government’s policies— ie, to brand them as members of armed communist guerilla movements, rendering them homo sacer in a regime of unbridled extrajudicial violence.

We turn to the present, the upcoming show. She’s developing a new version of a sound piece, built around the sound of bells, recordings, onomatopoeia, references, drawing from popular culture, excerpted sound recordings and other sources with a resounding knell being the primary refrain throughout the work. The piece comments on the Liberty Bell, itself a thing that fails to serve the purpose it was originally intended for, there but not there, and its place as a symbol of America as promise. When we imagine America, do we imagine ‘‘liberty’’? By drawing, across time, the sound of an un-ringable bell, she captures and gives form to the many presences of this phantom, one which had once drawn her family from its peripheries to the center of the empire. She tells me that because of the prevailing restrictions, she cannot realize the piece as it was originally intended—inside the bell tower of Christchurch, where the Liberty Bell would have hung. We can’t get too close to it. Instead, there’s a different idea: She’s been working with a group of bikers to disperse the piece throughout the city, making it resound through the streets, thus bringing into life the ossified symbol. The piece will ride through the streets with the bikers—there’s quite a culture of biker counterculture in Philadelphia, she tells me, of kids taking over the streets with their bikes, defying traffic, setting their own rules. It gestures back to the occupation of America’s streets in the on-going anti-racist, anti-fascist Black Lives Matter protests, and how this work, in such a form intersects with these. She will then restage it again with the collaboration of Farid Barron, a keyboardist for the SunRa Arkestra, who will drive around the Liberty Museum and Independence Hall, blasting the piece from his car. This also references the sonic occupation of American streets by POC (primarily black youth) with cars blasting music as a sign of defiance, of resistance, reenacted with the remixed sound of Liberty.

In recent weeks, the protesters have faced increasingly violent responses from the state, with police using decommissioned military grade equipment on protestors. The use of such violent tactics and technologies points precisely to the ways in which never disappear, but rather collapse in on themselves. Violence that was formerly directed outwards, gets directed towards its own body, instead. With the increased US withdrawal from global conflicts, more and more military equipment found its way into the hands of police departments and domestic security agencies. This in turn shape their responses to civilian movements, who therefore get framed as occupying enemy forces, or as ever-amorphous agents of terror, and are then dealt with accordingly.

There is a particular weight in this moment of the notion of a national symbol leaving its ossified confines to ride through the streets. Whose streets? Our streets. I think of the trajectory of the last 20 years of protests in the US. Of 2001, in Seattle, which produced the hopeful cry of ‘Another World Is Possible’. That was a moment of solidarities, of possible utopias. A future beyond that of neoliberal capitalism. Of 2008, when that same system produced another situation of collapse. The call then, too, was to occupy not only a space, but rather occupy finance itself, and therewith, occupy its ability to trade in our futures. Around that time, Judith Butler and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak entered into a conversation later published in a volume entitled Who Sings The Nation-state?[1], where they draw from the anti-racist protests in 2006, and the use of American nation symbols, such as the national anthem, and their deployment by immigrant communities almost an enchantments which could produce communities of belonging. The current movements present, however, an entirely different mood: one can argue that every march today in the streets of the US is only part of an extended funeral retinue, bodies gathering to add strength to the enactment of loss: a loss of black lives as well as the loss of a particular dream of America. The bells, tolling, rolling through the streets of Philadelphia, performing the sound of an unringable bell, seem to form part of this retinue, becoming a dirge to the nation-state itself.

[1] Butler, Judith, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Who Sings the Nation-State?: Language, Politics, Belonging. Seagull Books: 2007.

Abhijan Toto is Curator, Co-director, the Forest Curriculum, as s well as Curator, SAC, Subhashok The Arts Centre, and Artistic Director of 'A House In Many Parts’, both in Bangkok. He has previously worked with the Dhaka Art Summit, Bellas Artes Projects, Manila and Council, Paris. He is the recipient of the 2019 Lorenzo Bonaldi Prize at the GAMeC, Bergamo, his exhibition for which is currently on view, titled "In The Forest, Even The Air Breathes” on through February 14, 2021.

Tell me a story by Adam Kleinman

The poet Muriel Rukeyser once wrote that, ‘‘the universe is made of stories, not of atoms’’.[1]Personally, I’m more of a plumber than a poet, and in my crude understanding of things, I’ve always interpreted this to mean that narrative is the primary tool we use to make sense of the world. The thing is, storytelling is never neutral; for one, we speak in borrowed languages and forms, which are, of course, already embedded in larger systems. And while educators might use narrative to teach meaning, governments, the media, religions, and other power structures equally rely on storytelling to manipulate our very behaviors.

It could be said that climate change is the big story of today, however, I often wonder if the whole idea of writing for posterity is rendered pointless by it. No need to limit this to one existential threat alone; with the rise of AI, pandemics, a shaky global order predicated on inequity, and the ever-looming threat of nuclear war: another end of the world is possible. Everywhere you look, from reactionary politics pegged to nostalgia, to countless time travel memes that only plumb history on-line, it would appear that any future horizon is very far from our imaginary.

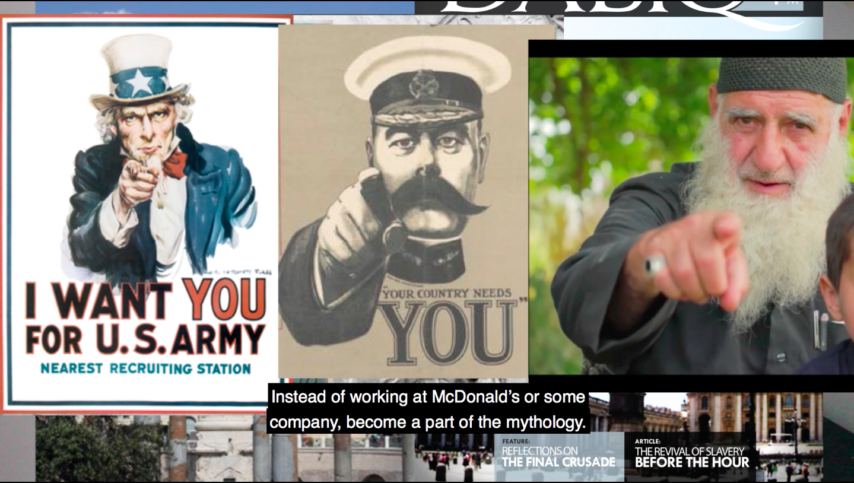

This brief jot is a short response to Hasan Özgür Top’s film, the Fall of a Hero (2020), a mock interrogation video in which an interviewee describes how zealots lure followers through a recycled ancient crusader myth: that the problems of the world are the result of society falling astray from an imagined golden age, and a return to grace is only possible if a righteous vanguard overthrows the forces that corrupt them. Top’s narrator is probably an unreliable one, but this is beside the point; I read him as simply a vector to deconstruct the uses and abuses of the hero narrative itself.

As a thought experiment, let’s turn this particular tale on its head by looking not at the past, but toward the very messy and clouded present we’re in for vehicles instead? It could go something like this: society and technology are grappling with unprecedented realties, and as such, you are living in the most influential time in all of history. Although I’ve shifted the vantage here, a peculiar vestige of that old script remains, namely an appeal to a narcissist, which centers the fate of the world on just one individual. We can do better.

If stories filter the world, it would be logical to think that a change in narrative can likewise shift the world with it. I may have gotten this backwards though. While we might be sitting at a unique hinge of history today, attention, so they say, has been shattered by the many digital devices, which push and pull each and all of us every and nowhere at the same time. Regardless of the message, tireless media spectacle drowns the present by fracturing any sense of continuity; could this be where the future was actually lost? Who really knows, but, for some reason, I, too, am pining for the past.

The hero’s journey, for what it’s worth, has been with the West for at least 4,000 years. These tales have survived translations, and cultures, and have morphed to serve both friend and foe with equal measure. They are widely attractive because they reflect our own time-based existence, however, the reproduction of narrative structure might have conditioned us to think that way. Tie this all to Aristotle if you like, who gave us the formula that stories, particularly those of political leaders, should follow a narrative arc through which some concluding statement about the point of it all is made so that its lesson can be learned. So, why are you here, and what is this whole note for?

Perspective, perhaps? Looking forward, or backward, or at the ‘‘now’’, is small potatoes; time, after all, has always been non-linear. The question to ask while hearing a story is: does it impose value onto the world, or does it dip into the caves of our shared memory to echo meaning from within?

[1] Rukeyser, Muriel. ‘‘The Speed of Darkness,’’ Out of Silence: Selected Poems. Edited by Kate Daniels, Northwestern University Press/TriQuarterly Books, 1994. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56287/the-speed-of-darkness, Accessed on 22 October 2020.

Adam Kleinman is Lead Curator for North America at KADIST, and an independent writer based in New York. He was previously Editor-in-Chief and Adjunct Curator at Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Agent for Public Programing at dOCUMENTA (13), and Curator at Lower Manhattan Cultural Council

Maya by Fawz Kabra

Have you ever wondered if our natural environment—the organic and physical matter surrounding us—senses our human-made traumas? Does it share in a society’s systemic amnesia or does it remember the various histories that have passed its landscape? Is there even a relationship among them? “It’s kind of a speculation mostly...”,[1] Burak Delier tells me, as he recalls the opening scene of Nuit et brouillard [Night and Fog] (1956), Alain Resnais’s documentary on Auschwitz. Delier describes the camera’s frame, capturing the sky and moving down towards a seemingly tranquil landscape, the growth of weeds points to the passing of time since the vegetation had sensed human activity. Now overgrown, the foliage peers back, a witness to the tremors of the past—it is an image that captures a profound phenomenon in itself.

In Istanbul, the neighbourhood of Kurtuluş is no tranquil landscape. When I lived on Kurtuluş Caddesi in 2010, the district was teeming with main streets and alleys, and countless steps winding around them that had been built and rebuilt over time. The movement of people, buses, cars and motorcycles, simit vendors, cake and ice cream makers never cease, drowning out the dark histories of persecution buried in the pockets of the city. The urban terrain, as with the rest of the city, has been in constant transformation as street names and population demographics have circulated and been replaced by the changing rule of law. Kurtuluş is the Turkish word for “emancipation,” which replaced the neighbourhood’s former name of Tatavla, which used to be known as a predominantly Armenian and Greek community, where the once celebrated city-wide annual Tataula Carnival concluded there in dance and celebration. The titular modification occurred with independence from the Ottoman rule and the forming of the Republic of Turkey. Delier tells me, “I always have this feeling when I come back to Istanbul, I feel that things are not rooted or connected.”[2]

Even the bakery that now serves bread made from Delier’s own cultivated yeast is a new, gentrifying establishment, taking over an older one that moved some blocks away. It is the site for Delier’s installation and intervention, Maya (2020). Meaning both “yeast” in Turkish and “illusion” in Sanskrit, Maya triangulates between a display of loaves of bread laid out in the shop window, a looped video screening the process of fermenting the yeast and making the bread, which is also served to customers at the shop. In the video, Delier records the yeast up close, bubbling and frothing as he exposes it to light and vibration. For two months, the yeast cultivated in a large glass container in the artist’s studio, attached to a surface speaker that senses vibrations. As it grew, the artist exposed it to videos and soundtracks, a combination of light and reverberation that stemmed from footage commemorating the massacres and pogroms in Turkey, the continuing persecution of Armenians, particularly the violence of September 1955 that targeted Greek communities throughout the city—especially in Kurtuluş.

The resulting montage is a layered critique that attempts to grasp trauma as it manifests in the suppression of its history by its own oppressor. Delier’s particular bread is a pedestrian sustenance. It is both living and political, a passive observer in the changing histories of the neighbourhood, which pulsate in its air bubbles and viscous medium. What do these histories taste like? Does the intensity of light or vibration from these events give the bread a distinct consistency? It is not transparent. The work deflects into a kaleidoscope of reflective planes: the screen of the monitor, the sound it emits, the visual plane of the yeast, the streets that lead into the bakery, and the online visuals that are abstracted by the artist, casting their stark light and resonating rhythms into the glutinous liquid.

With the national modernization, the bakery, too, modernizes and industrializes, serving bread baked in homogenous moulds; it does not boast centuries old yeast cultivated among generations of families. Maya,and its resulting bread, is both yeast and illusion. It attempts a process that situates itself in a trauma-based history of oppression and repression. The bread that is consumed and ingested, does it channel a haunted landscape within the current emancipated one? I returned to Resnais’s film and paused on the narrator’s contemplation on “those reluctant to believe, or believing from time to time, those who look at these ruins today, as though the monster were dead and buried beneath them, and those who take hope again as the image fades.”[3] Delier’s fermentation process attempts to absorb the histories that have been erased, but in the process, demonstrates the inability to claim the narrative(s). As these urban structures are demolished and replaced to cover up and reclaim what came before, the events of the past lose their definition, their hard edges blur, they become a sensation, a feeling, like the light and vibration that beats into the ferment and are kneaded into the dough, to finally get chewed up and swallowed.

[1] Video conversation with the artist; Wednesday, September 23, 2020. [2] Ibid. [3] Alain Resnais, Nuit et Brouillard (still), 1956, Argos Films, documentary short film [31:03].iversity Press/TriQuarterly Books, 1994. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56287/the-speed-of-darkness, Accessed on 22 October 2020.

Fawz Kabra is a curator and writer living in Brooklyn. She spent the summer of Covid-19 putting together Tame the Wilderness?, a zine concerned with community, art, and the environment.

Releasing the Old, Finding the New

by L. İpek Ulusoy Akgül

It was my first year of college, during an introduction to drawing class, when I experienced the 2003 Istanbul bombings. My whole body was shaken by the first blast in Şişli; when the second one took place in Beyoğlu four minutes later, my heart was racing and my ears could only hear the buzzing sound of the large-scale panes of glass that almost shattered into pieces. For some reason, we turned on the radio (yes the radio) and listened to the breaking news as we continued drawing. We were in shock, to say the least, and making art seemed to provide a good immediate coping mechanism. I did not know, at the time, that there were two more coming in five days.

All unresolved emotions, and the memories that are attached to them are stored in the body, and resurface until they are released for good, as they say. When I first saw the Beirut blast on the 4th of August this past summer on the social media account of an artist friend, it felt like reliving my own trauma of the Istanbul explosions, as well as that of the September 11 attacks, which I had watched on TV earlier. Was I triggered by seeing what was happening in Beirut? Yes. Was remembering my own experience a gesture of empathy for my friends and colleagues who were affected? Probably.

With a heavy heart and memories of my several trips to Beirut gleaming in the back of my mind, I type these words, "in response" to a recent intervention by one of those people: Stéphanie Saadé. The rise of grief during the pandemic, which fell on top of many crises all around the world, had taught us that without burning together there is no chance for collective healing. In other words, someone else’s pain is never someone else’s but always ours, and I knew that this text would not have written itself unless I was burning, too.

As I continue writing, I imagine that I am walking on the streets of the Marfa’ (port in Arabic) district before the explosion and that I am on my way to experience A Discreet Intruder (2020), a metal shutter shielding an empty storage. From the outside, the work does not shout, "Look at me!", like some interventions do. On the contrary, it "blends in" with the city as the bullet holes on the work appear rather mundane, even seamless to anyone local, who might have already become blind to the traces of the Lebanese Civil War. Thinking that, for any "outsider," the work might seem more brutal, compared to the artist’s previous installations, in terms of its artistic strategy -marks made with bullets akin to some examples of 1960s performance art- I trace an irregular map following the 38 bullet holes. Specifically pierced inside out, Saadé’s subversive and powerful work attempts to reverse the cycle of violence or return it where it came from.

A Discreet Intruder, also, functions on multiple levels - physical, philosophical and psychological - gently going back and forth between the personal and the collective, the private and the public. 37 of these holes represent the endpoints of significant routes taken by the artist between her birth in 1983 until the official end of the war in 1990 and another hole shows the departure point that is Saadé’s family home. From the inside, the experience is completely different. The aesthetics of violence are rather beautiful and surprisingly serene. The intimate map on the metal curtain transforms into a micro-universe here. We are exposed to a shifting constellation thanks to the dark interior of the storage space and the flickering sunlight coming in through the holes.

While speaking to Saadé’s childhood years, to which the artist’s "golden memories" refer to, it also responds to the ongoing pandemic, offering new ways of engagement with the public domain and a heightened sense of estrangement from one’s surroundings at a time of lockdowns and social distancing. Doing so, the work embodies the form intervention as it interacts with the existing structure or situation-the ongoing conflict in the region, pandemic, economic crisis and country-wide protests.

Let me now wake up to reality, to remember that Saadé’s work, which had been kept in storage in the port, was destroyed by the August 4 blast, along with the depot’s own metal curtain. Context-responsiveness gained yet another meaning as the site turned into ground zero and, the material, shattered into pieces, before the artist could actually puncture it with a gun and bullets. Our immediate tendency might be to say that the work was "lost" to the explosion. That would be valid. However, taking inspiration from the coexistence of vulnerability and strength that feed into the artistic process of Saadé, who often wanders on the borders of the tangible and the fleeting, persistence and ephemerality, life and decay in her practice, we might tackle a few questions: Can we consider the explosion as the moment when absence becomes presence for A Discreet Intruder? Was the work, in a way, "realized" with the blast? What does Saadé’s intervention manifest until it assumes a new body in the future? What has happened definitely adds new layers of meaning to the work until the point in time when it will be re-realized, and will probably continue to do so with each new experience. Until time reveals more about the life, transformation and rebirth of the work, we can simply try to digest the image of a depot without a shutter or dust.

[1] I am thinking of Stephanie Saadé’s The Encounter of the First and Last Particle of Dust (2019) and A Map of Good Memories (2015).

[2] See the works of Niki de Saint Phalle and Chris Burden, for example. A point to remember about Saadé’s intervention, here, is that only the signs of the shooting would be visible on the surface of the metal shield, and not the process of shooting itself.

[3] Genç, Kaya. "Stéphanie Saadé on the Beirut explosion and an artwork lost to the blast," Artforum, 14 September 2020. https://www.artforum.com/interviews/stephanie-saade-talks-about-an-artwork-lost-to-the-beirut-explosion-83896.

[4] Saadé points to this potential interpretation in Genç, Kaya. Ibid. Perhaps, we can also see this in relationship to or within the contexts of absence through destruction and presence via immediate media visibility of the Beirut port.

L. İpek Ulusoy Akgül is an independent editor, writer and curator currently based in Istanbul. She has recently been involved in the editorial processes of two upcoming publications for de Appel’s 2019 Curatorial Programme (CP) and Center for Spatial Justice’s (Mekanda Adalet Derneği - MAD). Previously, İpek has also edited Elif Uras’s monograph (2018), copyedited and translated for SALT (2017-18) and acted as managing editor of ArteEast Quarterly (2014-16).